Learning Objectives

- Describe hunger and sex as examples of drive reduction models of motivation

- Distinguish between primary (unlearned) vs. secondary (learned) and intrinsic vs. extrinsic motives

- Describe the levels of Maslow’s hierarchy (pyramid) of human needs

Emotion and Human Potential

Human behavior flows from three main sources: desire, emotion, and knowledge.

Plato

The Importance of Emotion and Motivation

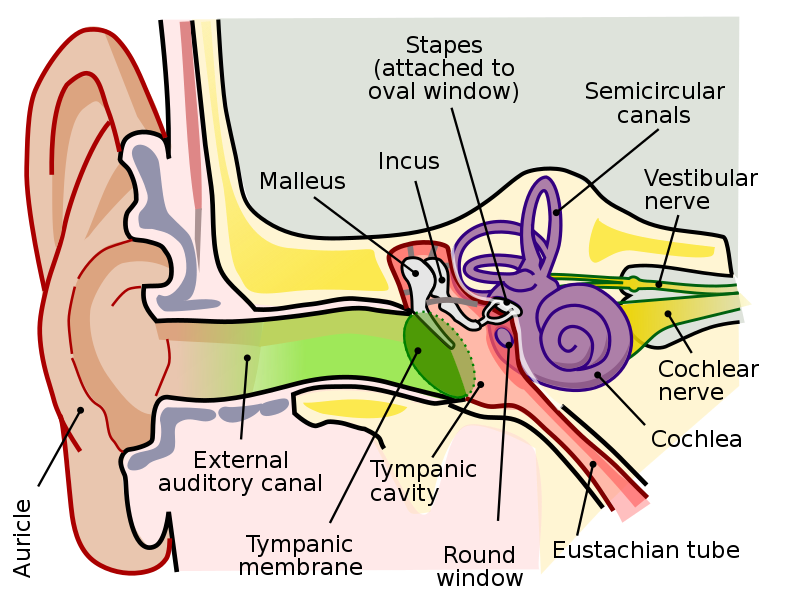

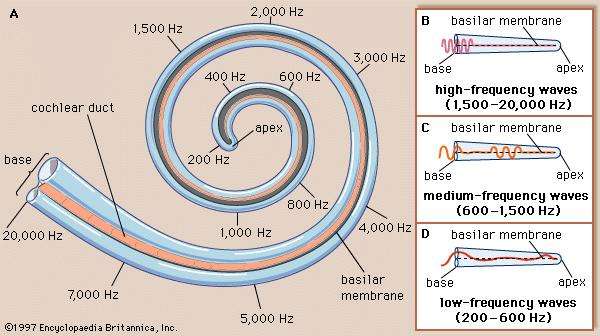

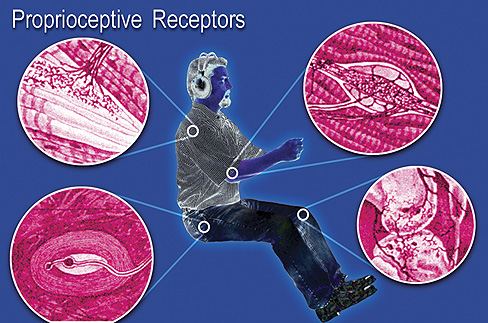

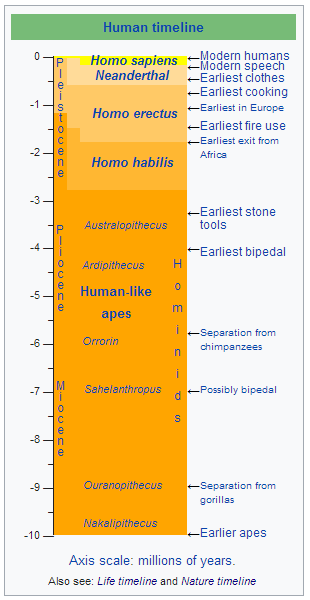

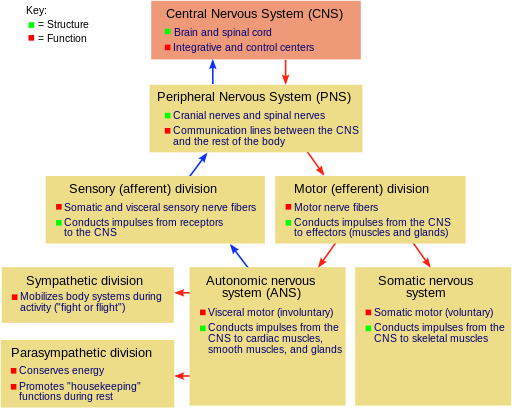

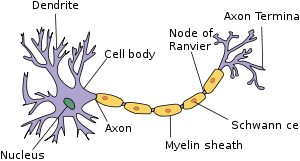

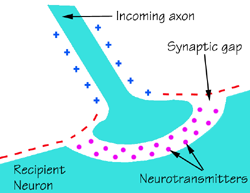

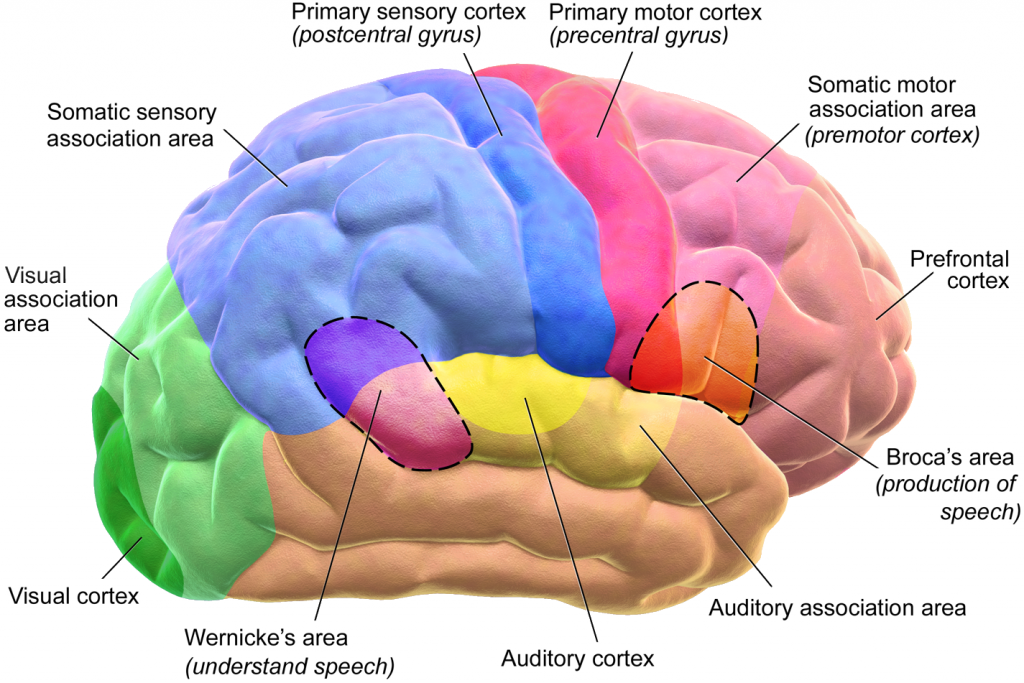

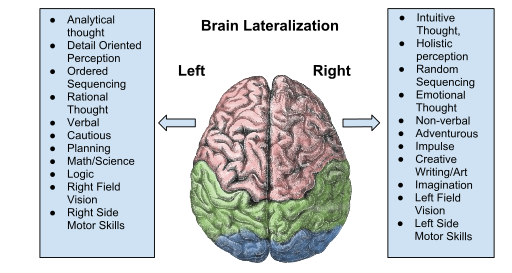

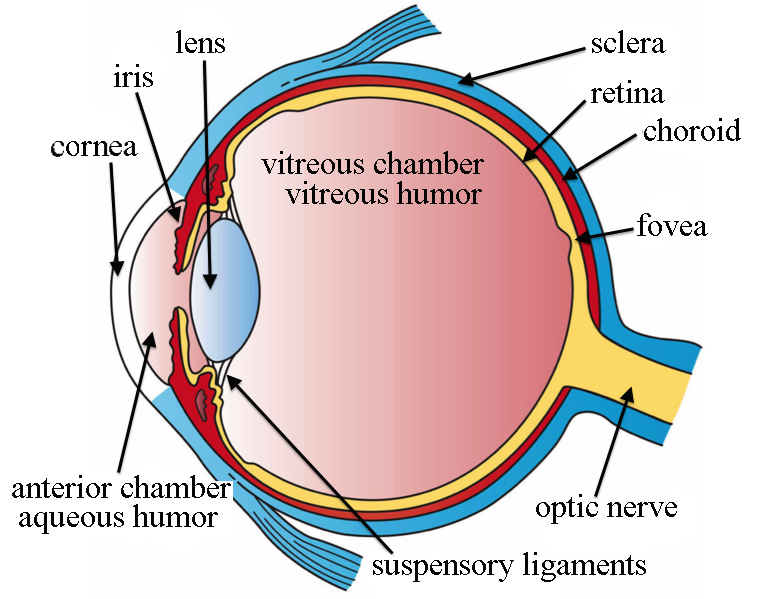

Chapter 4 is the third and last chapter in the Mostly Heredity section. In the biological psychology chapter, we emphasized the genetic evolution of the human nervous system, particularly the brain. In the following chapter, we considered how our nervous system transmits and interprets sensory information, relaying it to parts of the body capable of responding. The structure of our sense organs determined the raw sensory information which (with the exception of pain) was integrated and interpreted by the brain. Wundt and the structural psychologists considered sensations, images, and emotions to be the fundamental elements of conscious experience. Aristotle’s five senses (vision, hearing, taste, smell, and touch) respond to stimuli originating outside our bodies. The balance and muscle tension senses respond to stimuli originating from within our bodies. The current chapter addresses the sources of internal stimulation which determine our emotions. This stimulation motivates us to respond to our basic and higher human needs. Something has to make us want to eat, survive, and reproduce. Something must drive us to understand and transform our world and create things of beauty. As was true with respect to human perception, bottom-up and top-down processes are involved. There are biological sub-cortical underpinnings of our emotions and motivations which may then be influenced by higher-level, experientially-influenced cognitive processing.

Instincts as Explanation of Behavior

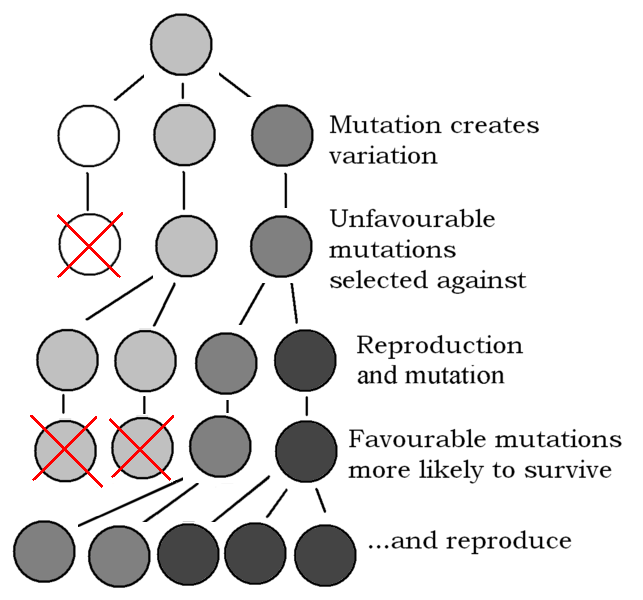

As described in Chapter 1, psychology studies the how heredity (nature) and experience (nurture) influence the behavior of individual animals, including humans. The early psychologists (Wundt, 1873; James, 1890) attributed much of human behavior, including emotions and motives, to heredity in the form of instincts. McDougall (1908) listed 18 instincts including those related to the bottom of Maslow’s human needs pyramid. Soon others began to expand the list. The term instinct became a pseudo-explanation for practically all behavior. Why do humans create things? Because of the creativity instinct. Why do humans speak? Because of the language instinct, etc., etc. A psychological explanation requires describing the specific genetic and/or experiential variables influencing a specific behavior. It is not sufficient to simply name a new instinct.

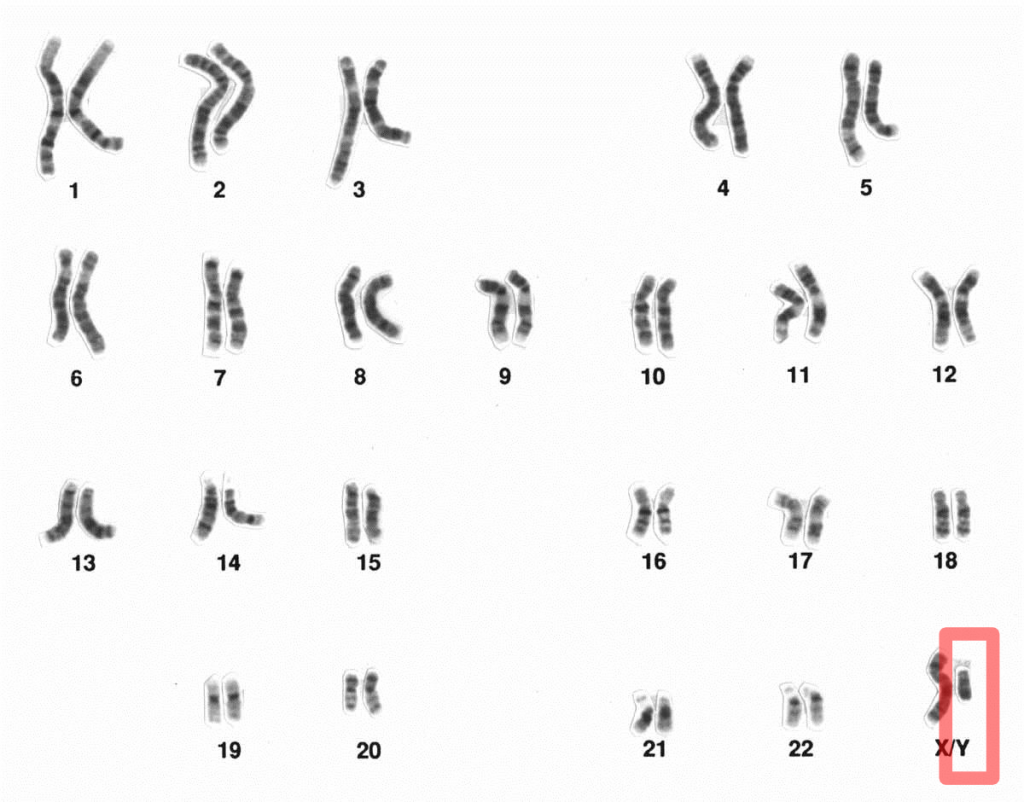

Many different definitions of the term instinct exist in dictionaries and textbooks. Combining the basic elements of these, an instinct is an unlearned, complex, stereotyped behavior, characteristic of all the members of a species. The word complex is included to exclude simple reflexes such as rooting and sucking in human infants or eye blinks and knee jerks in adults. Stereotyped behavior appears the same across different individuals within a species. For example, the web building of particular types of spiders, or the nest building of particular types of birds, appear remarkably similar. If we restrict the term instinct to behaviors fitting these criteria, one would be hard pressed to find a single example in adult humans. For example, how does one reconcile a maternal instinct with the fact that some traditional nomadic tribes engage in infanticide when an additional newborn cannot be carried on foraging trips (Diamond, 2012, 177-179). Tragically, in modern times it is not unheard of that a mother abandons or abuses her child. Much complex human behavior is taught in school and is not “unlearned.” Despite these and other strong arguments for abandoning instincts as explanations for complex human behavior (Herrnstein, 1972; Lehrman, 1953), the term persists. For example, the recently proposed “language instinct” (Pinker, 1994) fails to specify the specific human DNA (see Figure 1.2) or parts of the brain (see Figure 2.2) involved in the acquisition of speech or other forms of language (e.g., American Sign Language). The term instinct does not specify, and perhaps denies, the important role experience plays. The language we speak (or read, or write, or sign, etc.) is obviously influenced by where we are born and grow up. In Chapter 6, we will discuss the importance of the learning experiences involved in language acquisition.

Emotion

Darwin followed up The Origin of the Species with two other enormously influential and controversial books; The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex (1871), and The Expression of the emotions in man and animals (1872). These two works placed our understanding of human biology and psychology within the context of the rest of the animal kingdom. The first book distinguished between natural selection based upon inheritance of traits increasing the likelihood of survival and natural selection based on traits increasing the likelihood of mating. If a species were to survive, it was not enough for individuals to eat and avoid predators; some must also reproduce. We will consider the biology and psychology of sex later in this chapter. At this time, we will examine the important role emotions play in enriching our lives and influencing our survival as individuals and a species.

Darwin was a keen observer of nature. He concluded the facial expressions of different individuals reporting the same emotion were similar. He also thought there were similarities in the facial expressions of humans and other animals expressing the same emotion. He reasoned that emotions must be universally adaptive for them to have survived across different species of animals. Evidence in support of Darwin’s belief in the universality of human facial expressions was obtained for the seven different emotions shown in Figure 4.1 (Ekman and Friesen, 1971). Can you guess when the woman in the picture felt happy, sad, contempt, fear, disgust, anger and surprise?

Figure 4.1 Universal facial expressions for seven emotions.

There was great consistency across many literate and non-literate cultures in labeling the emotions shown in photographs depicting these seven emotions. Consistent with Darwin, Ekman (1993) also noted the similarity of the facial expressions of humans and other primates. Evolutionary psychologists have suggested that the universality of facial expressions for different emotions facilitates social learning. For example, a child (or monkey) could learn to fear an object by observing the facial expression of a parent. Ekman has since expanded his list of basic emotions to several others that were not as clearly differentiated with facial expressions. These included amusement, contempt, contentment, embarrassment, excitement, guilt, pride in achievement, relief, satisfaction, sensory pleasure, and shame (Ekman, 1999).

Biology, Thought, Emotion, and Behavior

Since its beginnings, the discipline of psychology has struggled with the relationship between human biology, thought, feeling, and behavior. As described in Chapter 1, human thoughts and feelings are not observable by others. The best we can do to study covert behavior is to obtain self-reports or make inferences based upon observable behavior.

For centuries, philosophers debated the roles played by reason and emotion in human behavior. Plato described the human being as being torn in different directions by two horses! Sigmund Freud, an extremely influential physician (he would currently be considered a psychiatrist), developed an elaborate personality theory based upon observations of his clients (Freud, 1922, 1923). He described the human condition as a conflict between basic needs and drives and the demands of one’s conscience.

Freudian, like Darwinian Theory, was enormously influential and controversial from its inception. The portrayal of the human condition as the struggle between temptation (sometimes portrayed as a devil on one shoulder) and conscience (an angel on the other shoulder) captured the imagination of the public and creative writers. However, the theory was developed and assessed tangentially to the science of psychology. For this reason, there has been confusion regarding how to interpret the theory’s implications or the effectiveness of its applications. To the extent that the theory generates testable hypotheses, it is appropriate to consider the results and implications of the evidence obtained. The Freudian theory of personality will be considered in Chapter 9 and his approach to abnormal psychology and psychotherapy in Chapters 11 and 12.

Traditionally, we consider human behavior to be influenced by emotion, reason, or both. Scherer (2005) listed five components of emotions including: a biological response; cognitive appraisal; motivational arousal; changes in facial and vocal expression; and subjective feeling. The behavioral components in Scherer’s list can be observed and measured, however the cognitive and feeling components cannot. The inferential nature of studying emotions sometimes leads to a “which came first, the chicken or the egg” problem.

Early in the history of psychology, William James made the counter-intuitive proposal that we label our emotions based upon our biological and behavioral reactions to stimuli rather than the other way around. In his words, “we feel sad because we cry, angry because we strike, afraid because we tremble, and not that we cry, strike, nor tremble because we are sorry, angry, or fearful, as the case may be” (James, 1884). This position was also being proposed at the same time by Carl Lange (a Danish psychologist), and since been labeled the “James-Lange theory of emotion.”

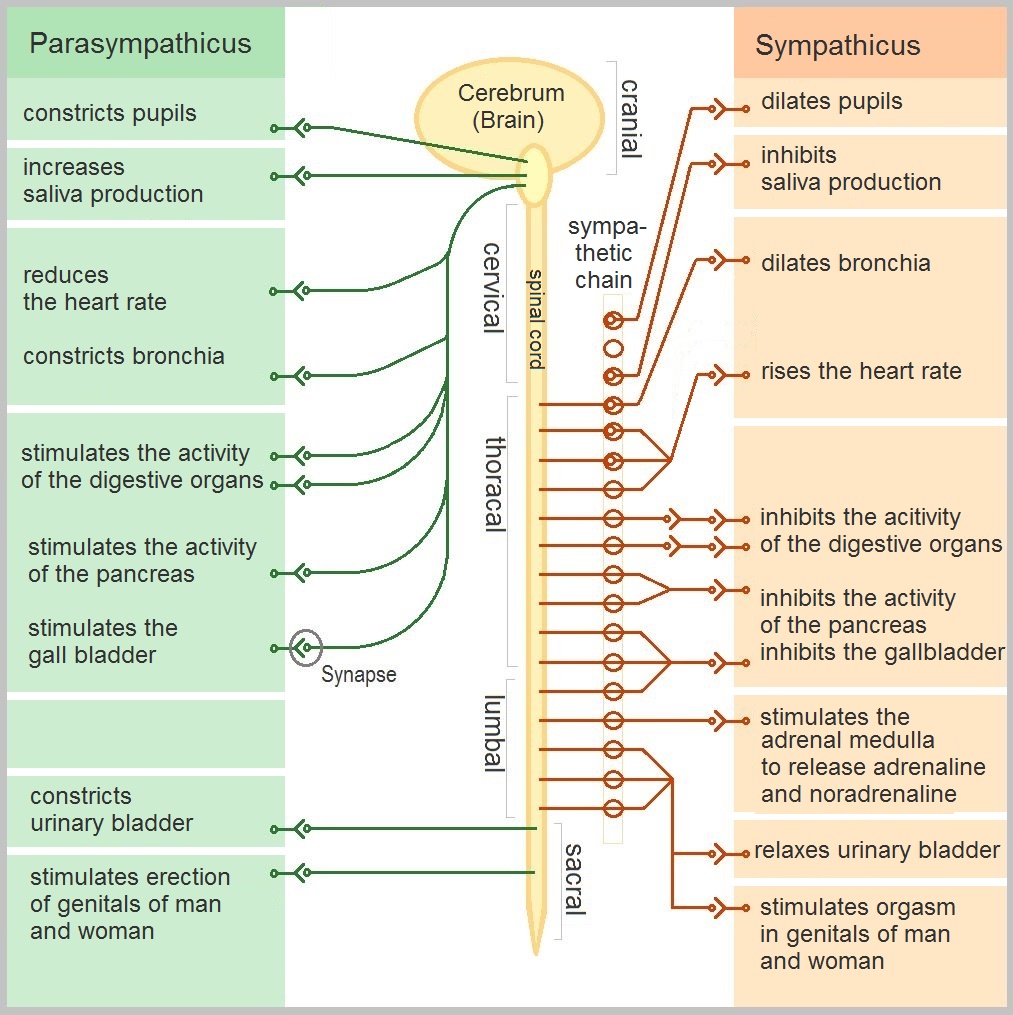

Walter Cannon (1927) argued that our emotional reactions occur too quickly and are too similar across different emotions to be the result of biological or behavioral responses. Phillip Bard (1928) obtained biological evidence consistent with this argument. He demonstrated that most sensory, motor, and internal autonomic stimulation first passed through the thalamus prior to higher-level processing in the brain. This suggests that autonomic arousal and our emotional response occur at the same time in reaction to an emotion-eliciting external stimulus. This position is called the “Cannon-Bard theory of emotion.”

In Chapter 11 (Social Psychology), we will describe attribution theory (Kelly, 1967). Here, we consider the two-factor theory of emotion, one of its important applications. This theory proposes that human emotions are based on a combination of bottom-up and top-down processing. The first stage consists of an emotion-eliciting stimulus resulting in a general state of autonomic arousal. The person then examines the environmental circumstances, attributing the arousal to a specific cause. The attribution then determines the label we apply to what we are experiencing. Schachter and Singer (1962) conducted an important experiment evaluating two-factor theory. College students were told they were receiving an injection to test their eyesight. Actually they were injected with epinephrine (adrenaline), a drug causing autonomic arousal. Some students were in the presence of a confederate (i.e., a person involved in the experimental manipulation) who acted in a euphoric (i.e., extremely happy) manner and others were in the presence of a confederate who acted angry. Students interpreted their feelings based upon the confederate to whom they were exposed, consistent with two-factor theory. These different emotional theories are described in the following video.

Human Motivation

Hedonic Motivation

As dissatisfaction grew with the attempts to account for human behavior by naming different instincts, psychologists shifted to explanations based upon the effects of emotions and motives. Today, when we try to answer the question of why someone did something, we frequently attempt to determine the motivation. We have seen how our nervous system transmits sensory information to the spinal cord and brain enabling adaptive responding. Some stimuli may be described as appetitive (or “good”). They typically elicit approach responses. In the case of painful stimulation, spinal reflexes immediately occur. It is as though our bodies evolved to protect us from stimuli which can cause tissue damage. Such stimuli may be described as aversive (or “bad”). They typically hurt and result in a withdrawal response. Appetitive and aversive stimuli elicit emotional responses and determine our motivation.

A simple hedonic model dates to the Greek philosophers and represents an early and straightforward approach to understanding human motivation (Higgins, 2006). It is basically a “carrot-and-stick” model assuming that one acts to seek pleasure and avoid pain. Variations on the hedonic model were postulated very early in the history of psychology by those holding very different perspectives ranging from Thorndike’s Law of Effect (1898) to Freud’s Pleasure Principle (1930). In Chapter 5, we will consider a contemporary adaptive learning model based upon hedonic principles (Levy, 2013).

Figure 4.2 Carrot and stick.

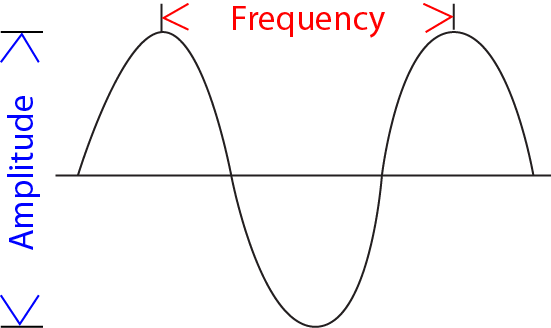

Motivation involves arousal and direction. That is, the individual’ state must change from rest to sustained action and address a specific condition (e.g., hunger) by achieving a specific objective (e.g., locating food). Maslow’s basic biological needs provide clear examples of motivated behavior. When deprived of food, humans will engage in “hunting and gathering” behaviors until finding (in the wild or in the cafeteria) a sufficient supply. When confronted with danger, humans will exhibit defense reactions until escaping. For example, if a mouse is attacked in the wild, it will probably immediately try to run away. Upon sexual arousal, animals will engage in courting and copulation. The basic survival needs at the bottom of Maslow’s Human Needs pyramid act in a manner consistent with a drive-reduction model of motivation (Hull, 1943). The assumption is that deprivation of appetitive stimuli or presence of aversive stimuli will arouse and direct behavior until the drive is satisfied.

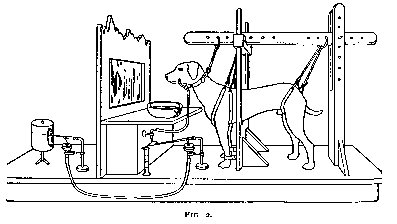

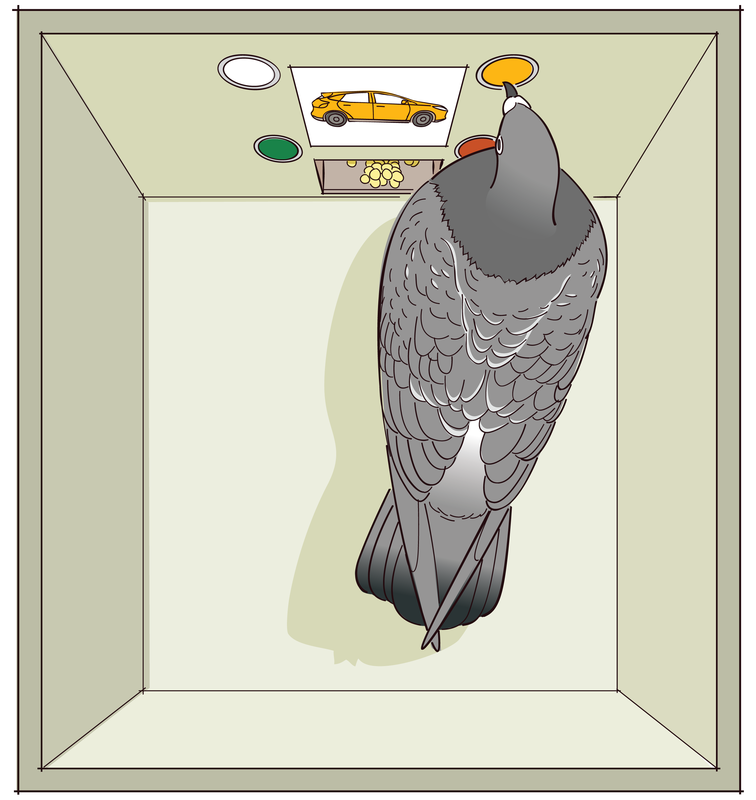

Separate studies have been conducted with rats evaluating whether deprivation of an appetitive substance arouses behavior and whether it directs behavior. It would be unethical to intentionally deprive human subjects. Such procedures are permitted with other animals as long as justification is provided and strict protocalls are followed. The US government and American Psychological Association have strict ethical guidelines for conducting research with non-human subjects. These guidelines apply to deprivation procedures as well as those involving aversive stimuli. Laboratory animals typically have much safer and comfortable environments than those living in the wild. For example, rats and pigeons do not have free access to food in nature and are usually in a state of mild, if not severe deprivation most of the time. The level of deprivation maintained in the lab is actually low in comparison to that typically experienced in the wild.

The simplest research procedure used to systematically manipulate deprivation is to control the amount of time till the individual is provided the substance (e.g., food, water, etc.). For example, food may be withheld for 3, 6, 9, or 12 hours. A complicated but more sensitive procedure is to maintain the individual at a percentage of its free-feeding body-weight (i.e., weight when provided free access to the stimulus). Collier (1969) manipulated rats’ weights by depriving them of food and studied the relationship between level of deprivation and the number of turns on a running wheel (see Figure 2.16). As deprivation increased, the amount of activity in the running wheel increased. At first glance, this may seem maladaptive. One might expect animals to conserve energy if deprived of food or water. Whenever one observes this type of counter-intuitive observation it is often productive to consider how the behavior might be adaptive in nature. In the running wheel, despite its best efforts, the animal “goes nowhere fast.” This is not the case in nature, where movement from place to place will increase the likelihood of discovering the appetitive stimulus. In any event, the results are clearly consistent with the drive-reduction model of motivation; deprivation definitely served to arouse behavior (i.e., the rats ran more).

A study demonstrating the second assumption of the drive-reduction model, that deprivation directs behavior, was conducted using a straight runway. Those observing rats in different laboratory apparatuses frequently see them engaging in many behaviors such as sniffing, grooming, and exploring the apparatus. When this occurs in a situation where it interferes with the animal’s obtaining a reward, such behaviors are described as competing responses. In a study manipulating hours of food deprivation, Porter, Madison, and Senkowski (1968) demonstrated a reduction in competing responses as a function of level of deprivation. That is, as deprivation increased, the rats were less likely to explore the runway and their behavior became more goal-directed. This is consistent with the drive-reduction assumption that deprivation of an appetitive substance will direct animal’s behavior toward obtaining the substance.

The Biology and Psychology of Hunger

One of the very best things about life is the way we must regularly stop whatever it is we are doing and devote our attention to eating.

Luciano Pavarotti

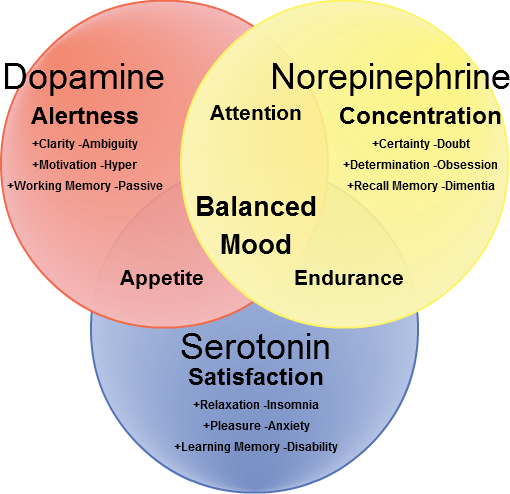

According to the drive-reduction model, you eat because you are hungry. Consuming food reduces the hunger drive, resulting in feeling full (i.e., satiation). Hunger pangs result from contractions of stomach muscles and usually do not occur until going 12 or more hours without food. Rising glucose levels, amino acids, or fatty acids in the blood, result in secretion of the hormone leptin, reducing your desire to eat (Suzuki, Jayasena, & Bloom, 2011). The effect of leptin wears off after a few hours and eventually secretion of the hormone ghrelin causes you to feel hungry again (Malik, McGlone , Bedrossian, & Dagher (2007). Leptin and ghrelin influence hunger by stimulating the hypothalamus in the limbic system. Studies with rats have found that damage to different parts of the hypothalamus result in either loss of the desire to eat or in excessive eating (Neary, Goldstone, & Bloom, 2004).

The title of this section is “Mostly Nature.” In the previous chapter, we saw the important role experience plays in determining how we perceive the world. Now we will examine the role experience plays in influencing our motivation. The biological causes of hunger are based on our genetics (i.e., nature). Other factors causing us to be hungry are based on our experiences with food (i.e., nurture). In Chapter 5, we will describe direct learning experiences in which associations are formed because of the predictability of events. If you develop a daily pattern for consuming meals or snacks, eventually you will start to feel hungry in anticipation of the time when you usually eat. Similarly, if you associate eating with particular people (e.g., a significant other or friend), places (e.g., the cafeteria or a favored restaurant), or events (e.g., attending or watching a game on TV), you may feel hungry when with the person or experiencing (or even imagining) the place or activity.

Food does not just reduce the hunger drive. Humans enjoy the taste and smell of food. Since eating is pleasurable, some cope with unpleasant emotions such as depression or boredom by consuming food. Humans have a genetic preference for sweet and fatty foods which are dense in calories and efficient sources of energy (Keskitalo, et al., 2007). This preference served us well as nomadic hunter/gatherers in environments in which supplies were scarce. Industrialization has enabled us to produce food surpluses and create all sorts of tasty snacks. This has the benefit of helping address world hunger. Unfortunately, it also means that it is relatively easy to consume an excessive amount of calories. Many industrialized nations, including the United States, are experiencing unprecedented levels of childhood and adult obesity as the result (Popkin, 2007). Obesity is not a problem for present day humans living as nomads in the rainforest or desert. They aren’t able to produce food surpluses and don’t have fast food restaurants or tasty junk foods. Nomads also get plenty of exercise!

Hunting and Gathering in the Rainforest and Supermarket

Gustavo Politis (2007) reported the results of anthropological research conducted on the Nukak tribe in the Columbian Amazonian rainforest between 1990 and 1996. The Nukak are anatomically and physiologically the same as we are. They share the same needs to eat, survive, and reproduce. Women bear children, and along with elders of both genders, assume primary responsibility for nurturing and socializing them.

Women participate somewhat in hunting and gathering for food but spend more time in food preparation. Nukak foraging trips generally last much of the day (between nine and ten hours) and usually are conducted by adult males, sometimes accompanied by adult women and/or older children. Trips often cover distances approaching ten miles, back and forth. The products consist of fruit, vegetables, honey, and sources of protein such as turtles and squirrel monkeys. These foraging trips are similar to those made for the past thousands of years. Most elderly adults, young women, and children, remain in the camp. Young children may collect water from nearby watering holes as their contribution to the survival needs of the camp.

The Nukaks’ rainforest conditions, in contrast to our technologically enhanced circumstances, pose very different challenges. For thousands of years the Nukak lived in a relatively predictable and controllable environment. They have had time to experience and adjust to the intricacies of the rainforest and transmit their knowledge and skills to each other and their children. We live in an ever-changing environment but have the advantage of continually accumulating knowledge and technologies. Every day, Nukak band members travel several miles to forage for unknown quantities and varieties of locally-available food. In contrast, it would take us less than an hour to shop in a supermarket for a week’s worth of food from all over the world!

The Nukak pick up and move every 4-5 days, constructing between 70 and 80 campsites each year, almost never reoccupying an abandoned camp. One benefit of this mobility pattern is the creation of future sources of edible plants. The seeds left from previous occupancy result in larger and denser patches of fruit than typically occur in the rainforest. Thus, the Nukak practice a form of migratory agriculture, literally laying the seeds for future foraging trips (Politis, 2007, 114-119). Campsites are located next to resources at those times when they are abundant throughout the year. For example, fish are more abundant during the dry season; during those months campsites are usually established near waterways and streams (Politis, 2007, 281-283).

A campsite consists of an average of four functional units, each accommodating a nuclear family and perhaps one or two close relatives. Every functional unit includes at least one central hearth, providing heat for cooking, tool-crafting, and warmth. Hammocks are hung from the trunks of medium-sized and small trees. In the rainy season (8 months of the year), roofs are constructed of platanillo and seje leaves (Politis, 2007, 100-103). The Nukak perform most daily activities near the hearth while seated in the hammocks.

Establishing a new camp takes no more than a couple of hours and is mostly conducted by the men. Nukak camps are designed for providing warmth when needed, effective ventilation, and cover during the rainy season. They are not designed for protection from predatory animals or other humans. There were no known instances of attacks by jaguars or other carnivores (Politis, 2007, 124). The camp is designed so that the individual shelters housing the separate families are inter-connected without separating walls. This permits the members of the band to protect each other from spirits at night. It also eliminates privacy, resulting in most intimate sexual activity occurring during the day on foraging trips (Politis, 2007, 124).

The Nukak traditionally live almost all of their lives in these small camps located within a 240-to 300-square mile portion of the Amazonian rainforest (Politis, 2007, 163). Living in this manner facilitates communication and sharing of food, water, firewood, and other substances required for survival and comfort. Periodically, the Nukak visit bands, often consisting of kin, located within a wider, tribal region of approximately 600 to 1,200 square miles. The population density is such that tribes in the Nukak’s region of the Amazonian rainforest do not compete for land or resources. There is no evidence of conflict or inter-tribal aggression (Politis, 2007, 180).

Many of us live for years in enclosed, secure apartments and homes in policed neighborhoods. It is ironic that we may be less safe than the Nukak in their temporary, open camps in the unguarded Amazon. Population densities in the Nukak’s section of the rainforest consist of perhaps a few dozen people per square mile. Some of our cities have population densities in the tens of thousands per square mile! The Nukak live amongst their kin and close relations, all of whom depend upon each other to survive. For us, industrialization has resulted in movement from sparsely-populated rural areas to crowded urban centers. Increasingly, people live among strangers with a diversity of needs, interests, and values.

Domestication of plants and large animals enabled humans to abandon the nomadic lifestyle and settle in one location. Larger and larger communities formed and there was increased competition for resources. There became a need for collective security. Hunting weapons originally developed during the Stone-Age, such as the axe, spear, and bow-and-arrow, became tools of self-defense and war. Evolutionary biologist Jared Diamond wrote a wonderful Pulitzer prize-winning book tracing the history of the human being leading up to and after the last ice age, approximately 13,000 years ago. He describes how features of the climate and environment impacted on the course of development of humans on the different continents and why some cultures eventually became dominant over others. The revealing title of his book, Guns, Germs, and Steel (Diamond, 2005) describes the important impact this had on the current human condition for cultures as distinct as the Nukak and us.

Survival of our species: The Biology and Psychology of Sex

And that’s why birds do it

Bees do it

Even educated fleas do it

Let’s do it, let’s fall in love

Let’s Do It, Cole Porter

We don’t know if birds, bees, and fleas fall in love. We do know they engage in sex or they wouldn’t be here. The hunger and sex drives are very primitive, having existed in mammals for millions of years. Unlike hunger, the sex drive is not present at birth. Unlike eating, you do not have to engage in sexual activity in order to survive. However, some of us must do so in order for the species to survive.

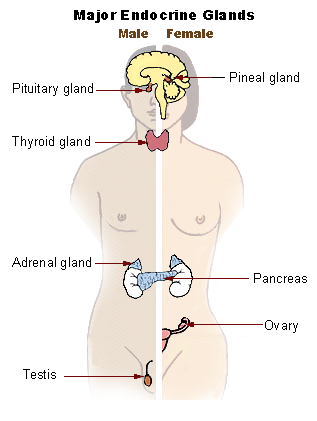

Chapter 8 describes the physical and psychological changes characterizing the lifespan of human development. For practically all of our history, no matter where humans existed, the only meaningful distinction in developmental status was between childhood and adulthood. The stages were demarcated by initiation of the sex drive and the ability to reproduce toward the end of puberty. The significant major indicators for the onset of puberty are the first menarche (i.e., period) for females and ejaculation for males. Puberty typically lasts approximately five years and starts one year later for males than females. The physical changes resulting from puberty are initiated by the hypothalamus secreting lutenizing hormone releasing factor. This stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete the gonadotropic hormones LH (lutenizing hormone) and FSH (follicle stimulating hormone). The gonads (i.e., sex glands; ovaries in the female and testes in the male) start increasing in size until the end of puberty.

Drives arouse individuals and direct their activity. As seen previously, deprivation of food increases activity and the likelihood of discovering something to eat. A painful stimulus elicits a withdrawal response, decreasing the likelihood of suffering a serious injury. At the end of puberty, deprivation of sexual stimulation arouses and directs humans to engage in sexual activity (e.g., intercourse, masturbation, etc.).

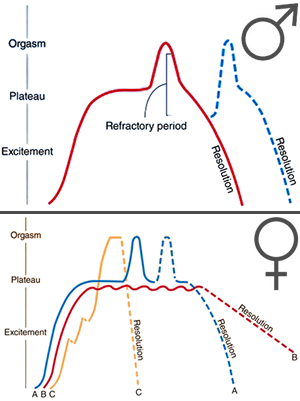

Masters and Johnson (1966) physiologically recorded the sexual activity of over 300 male and 300 female volunteers for eight years. The subjects consisted mostly of white, highly educated, married couples. This pioneering research led to formulation of the four phase human sexual response cycle shown in Figure 4.4.

Figure 4.3 Sexual response cycle.

During the excitement phase, heart rate increases and blood flows to the genitals resulting in swelling of a women’s clitoris accompanied by vaginal lubrication, and erection of a man’s penis. In males, erotic stimulation can result in a partial erection within a matter of seconds. In women, the excitement phase usually lasts for several minutes and can be extended for lengthy periods of time, even hours. During the plateau phase, the biological changes increase in intensity until orgasm is achieved. Orgasms last only a few seconds and consist of involuntary muscle contractions, a building and sudden release of sexual tension, and ejaculation of semen by men. During the resolution phase, the body gradually returns to its state prior to excitement accompanied by calm, pleasant feelings. Women are capable of repeated orgasms; however men must usually wait a while before being able to obtain an erect penis and ejaculate again.

Males and females are socialized differently to assume their defined sex roles at the end of puberty. Much of that socialization relates to eating, surviving, and reproducing. There are substantial cultural differences in the treatment of sexuality. Unlike most technologically-enhanced cultures, traditional nomadic Stone-Age tribes treat sex in a matter-of-fact manner. It is expected that upon completing puberty, a suitable mate will be identified, couples will be formed, and they will have children.

Nukak couples are mostly monogamous (approximately 85 % in two samples taken in the 1990s) with some men having two wives. Cross-cousins (i.e., cousin from a parent’s same-sex sibling) are the preferred partners with marriage between parallel cousins (i.e., cousin from a parent’s opposite-sex sibling) being prohibited. Although the stated norm was for the woman to live with the husband’s family, in practice living arrangements appeared to be flexible in the 1990s (Politis, 2007, 81-82). This may have been the result of sudden reductions in population resulting from contact with the outside world starting in 1988. Nukak bands travel periodically so that members may visit (frequently kin), searching for potential mates (Politis, 2007, 80-81).

For several decades, cross-cultural research has indicated that approximately 90 per cent of individuals all over the world get married (Carrol & Wolpe, 1996). The idea that there is only one perfect spousal match is certainly truer for the Nukak than for us. It is very unlikely that there are many cross-cousins of the right age and gender among the Nukak bands in the rainforest, the entire population numbering less than 500. Contrast that with the number of potential partners you might meet on Facebook! Actually, the idea of romantic love as the basis for marriage is relatively recent. “In most cultures throughout history, marriages have been arranged by parents, with little regard for the passionate desires of their children” (Arnett, 2001, 267). Buss (1989) conducted a monumental study of over 10,000 young people in 37 different cultures representing all the continents except Antarctica. There was striking consistency across cultures in the most important factors in mate selection. Both males and females considered “love” (i.e., mutual attraction) first, followed in order by “dependable character”, “emotional stability and maturity”, and “pleasing disposition.” It would certainly seem an evolutionary challenge for two people to find one another given the complexity and difficulty of this search. However, the fact that 90% of us eventually marry, happily indicates that it is usually possible to locate potentially desirable mates.

Sleep

We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

The Tempest, WilliamShakespeare

After spending the day hunting and gathering, preparing meals and taking care of the kids, and perhaps sneaking in a little reproduction time, it should not be surprising that the Nukak spend the remaining third of their day sleeping. Sleep possesses the characteristics of a basic drive. As portrayed in Figure 4.5, deprivation leads to an increased need for and urge to engage in sleep. The need for sleep is a straightforward function of how long it has been since waking (6:00 a.m. in the figure). The need similarly declines linearly once the person goes to sleep (10:00 p.m. in the figure).

The hypothalamus acts like a biological clock in regulating some life functions, including sleep (Abrahamson, Leak, & Moore, 2001). Destruction of specific cells in the hypothalamus will result in loss of a sleep-wake cycle. Circadian rhythms consist of approximate 24-hour cycles which may be influenced by environmental events. The urge (i.e., feeling) that one needs to sleep is based on the circadian rhythm caused by day-night cycles and secretion of the hormone melatonin by the pineal gland (Benloucif, Guico, Reid, Wolfe, L’hermite-Balériaux, M., & Zee, P. C., 2005). . The urge is highest at approximately midnight, declines till about 10:00 a.m. and then rises to a moderate peak around 2:00 p.m. before dipping again. This mid-afternoon rise is probably the reason for the mid-afternoon naps practiced by some cultures.

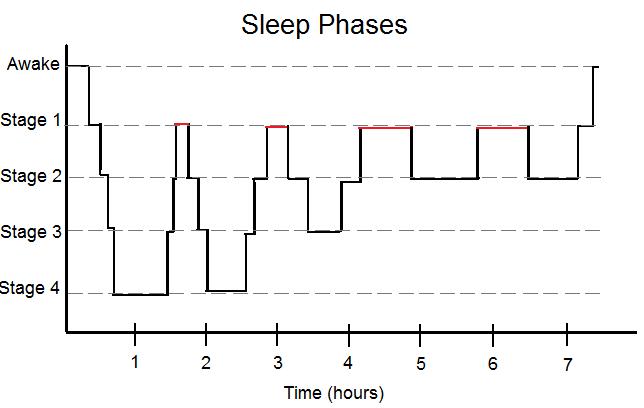

Interestingly, the effects of deprivation are more specific than simply increasing the likelihood of sleeping. An adult’s sleep pattern consists of cycles of four different stages (see Figure 4.4). Deprivation can be specific to any of these stages (Silber et al., 2007). For example, if deprived of REM (rapid eye movement) sleep (stage 1) or deep sleep (stage 4) and able to rest, one will immediately enter an extended REM or stage 4, rather than starting with stage 1. It seems one not only needs a certain amount of sleep, but a certain amount of the different stages of sleep.

Figure 4.4 Stages of sleep.

There are usually four to five complete cycles each night. Typically, the deep sleep stages of each cycle last longer the first times they occur and the REM stages last longer the last times they occur prior to waking up. The dreams one remembers practically all occur during REM sleep which is accompanied by deep muscle relaxation, bordering on paralysis. Research with rats suggests that this paralysis is the result of two neurotransmitters acting upon the motor cortex. It is thought that in humans, this paralysis protects us from acting out the contents of our dreams (Brooks & Peever, 2012).

Even people who believe they do not dream may be shown to do so when studied under laboratory conditions (Dement 1974). The contents of dreams are influenced by one’s culture. The dreams of the Nukak are more likely to include animals than the dreams of those living in contemporary cities (Domhoff, 2001). For the most part, dream content does not appear as exciting or romantic as often portrayed. Rather, the content appears to reflect everyday events such as eating, being with friends, taking exams, or trying to solve problems (Domhoff, 2003).

What’s It All About?

Yesterday a child was filled with wonder

Caught a dragon fly inside a jar

Fearful when the sky was full of thunder

And tearful at the falling of a star

The Circle Game, Joni Mitchell

The first and simplest emotion which we discover in the human mind, is curiosity.

Edmund Burke

The opening stanza of Joni Mitchell’s song reminds us of children’s innate curiosity. From the beginning, humans are awed by their surroundings and try to understand what they observe. Not all human behavior appears to fit a drive-reduction model of motivation. Why do we play games, solve puzzles, and explore nature as children and adults? Why do we ask ourselves “What’s it all about?” To account for such behaviors, some have postulated an “effectance” (i.e., need for competence) drive (White, 1959), or a “curiosity” drive (Berlyne, 1960). These are considered drives based on the assumption that they are activated under low levels of stimulation (i.e., sensory deprivation) in the same manner that the hunger and sex drives occur after deprivation of food and sexual stimulation (Tarpy, 1982, 318). If deprivation is not necessary, the term “drive” would pose the same problem as we observed with the term instinct as an explanation for a multitude of behaviors. Drive would just be a label for the behavior it is purporting to explain. It would not specify the relationship between an independent variable (a specific type of deprivation) and a specific behavior.

The drive reduction model of motivation appears to adequately account for the basic biological needs we share with the rest of the animal kingdom. The model also appears adequate to understanding the motivation for practically all human behavior under our original nomadic Stone Age conditions where life was a day to day struggle to survive. However, we have transformed the human condition such that school and/or work now comprise substantial parts of our lives. What sort of motivational model applies to schools and the workplace?

Motivation as State and Trait

Drive-reduction models consider motivation to be a state induced by environmental conditions. Motivation occurs and increases as a function of deprivation of an appetitive substance or the presence and intensity of an aversive stimulus. Chapter 9 describes different approaches to assessing and understanding human personality. Some approaches describe personality as consisting of traits, including different types and levels of motivation. Henry Murray developed the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT) to assess individual personality traits (1938). The TAT consists of a series of ambiguous pictures of people in different situations.

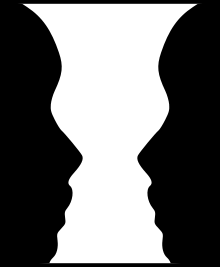

You may recall examples of top-down processing from Chapter 3 in which one’s prior experience influenced the interpretation of ambiguous stimuli. The TAT is an example of a projective technique in which it is assumed that an individual will interpret and describe pictures of ambiguous social situations based upon their own personal needs and motives. Usually between eight and a dozen of the 32 pictures are selected by the researcher or practitioner. The person is asked to develop a narrative including what happened prior to the events depicted, what is happening in the picture, what the individuals shown are thinking and feeling, and what happens afterward. Murray inferred that individuals differ in levels of the need for achievement (nAch) based upon their responses. Many included narratives describing: “intense, prolonged and repeated efforts to accomplish something difficult. To work with singleness of purpose towards a high and distant goal. To have the determination to win” (Murray, 1938, 164).

Primary and Secondary Motives

A distinction is sometimes made between primary (sometimes referred to as biological or unlearned) and secondary (sometimes referred to as psychological or learned) needs, drives, or motives. David McLelland (1958) followed up Murray’s research, modifying the scoring of the TAT and relating the findings to motivation in school and at the worksite. McClelland inferred the existence of three different psychological needs; achievement, affiliation, and power.

McClelland inferred a high need for achievement (nAch) from TAT narratives emphasizing competitive themes and expressions of the desire to excel in activities of personal interest. Those low in nAch often expressed fears of failure. They pursued very easy tasks where they were unlikely to fail or very difficult ones where they would not be embarrassed by failure. In contrast, those scoring high in nAch sought out moderately difficult tasks which were challenging but possible. Students with high nAch scores tend to perform better in school (Raynor, 1970). High nAch workers indicated being more extrinsically motivated by social recognition of their accomplishments than low nAch scorers who appeared more concerned with money and other tangible rewards. McLelland believed (and research supports) the important role of parenting and socialization in developing achievement motivation. Parents of high nAch individuals encourage independence, teach goal-setting skills, praise and reward demonstrations of effort and success, and attribute accomplishment to competence rather than luck (McClelland, 1965). McLelland inferred a need for affiliation (nAff) from narratives emphasizing the importance of getting along with others and maintaining harmony. Hi nAff scorers prefer work situations involving a high degree of interpersonal interaction. Those with a need for power (nPow) produce narratives emphasizing the need to influence and control others’ behavior. At the worksite, high nAch scores have been found to correlate with persistence (McClelland, 1987) and with success in low level management positions. Those motivated by power, however, were more likely to succeed in high level leadership positions (McClelland & Boyatzis, 1982).

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Rather than distinguishing between primary and secondary sources of motivation, some have made the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic sources of human motivation (Hunt, 1965). That is, humans appear to engage in many complex tasks due to the stimulation resulting from the activity itself. This is different from engaging in an activity in order to obtain a different stimulus, be it food, a gold star, or money.

Data suggest that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation decline gradually over the course of one’s school years (Harter, 1981; Sansone & Morgan, 1992; Lepper, Henderlong, & Iyengar, 2005). Some have suggested that reliance upon extrinsic rewards for learning (e.g., test grades and awards) is at least partially responsible for this decline. Others cite over-reliance on high-stakes standardized tests, a lack of relevance of the material to students’ everyday lives, as well as other factors for this steady decline in motivation.

There is controversy concerning whether dispensing extrinsic rewards undermines intrinsic motivation (Sansone & Harackiewicz, 2000). In an often cited seminal study (Deci, 1971), intrinsic motivation was assessed in college students by observing the amount of time spent performing different activities when no extrinsic rewards were provided. The subjects were randomly divided into two groups. Three daily sessions were conducted in which the students were timed while trying to produce four different patterns on a cube puzzle. In the second session, one group received a dollar for each puzzle solved within the allotted time. The experimenter left the room for eight minutes during each of the daily sessions and the subjects were told they could do whatever they liked. The subjects in this group increased the amount of time spent working on the puzzle from the first to the second day but spent less time working on the puzzle on the third day than they did on the first day. This pattern was not observed in the control condition which did not receive a monetary reward on the second day. Deci described this apparent undermining of intrinsic motivation by extrinsic rewards as an overjustification effect. That is, focusing upon extrinsic rewards diverts attention from the intrinsic rewards generated by the activities themselves. This is thought to result in a temporary increase in motivation for performing the task. When the extrinsic reward is eliminated, there is still decreased attention to intrinsic rewards, resulting in the observed decline in time spent on the activity. In a second experiment reported by Deci, it was shown that the time spent on the puzzles continued to increase when verbal praise rather than money was provided for correct responses on the second day. Praise, which can also be considered an extrinsic reward, apparently does not distract the individual from intrinsic sources of motivation.

Deci’s original findings and conclusions generated considerable controversy as well as a substantial research literature. A 25-year review concluded that the effects of providing extrinsic rewards for performing a task are varied and complex (Lepper & Henderlong, 2000). When performance standards are set low or are vague, extrinsic rewards have been found to reduce performance of the task. However, when standards are set high and described clearly, extrinsic rewards have been found to increase intrinsic motivation (Eisenberger, 1999). Another summary of the research literature concluded that the overjustification effect was limited to Deci’s free-time measure. When actual task performance was measured, extrinsic rewards were found to enhance rather than undermine intrinsic motivation (Wiersma, 1992). It has also been found that subjects displaying high degrees of intrinsic motivation are unlikely to demonstrate an overjustification effect (Mawhinney, 1990). It now appears appropriate to conclude that it is desirable to encourage intrinsic motivation. If implemented effectively, extrinsic rewards can be helpful toward this end. Just as perceptual phenomena are affected by prior experience, the same is true with motivational phenomena. Motivation is influenced by the ways in which extrinsic rewards, including praise, are administered at home, in the classroom, and at the worksite.

Motivation and Human Potential

Putting it All Together: Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs

Classic economic theory, based as it is on an inadequate theory of human motivation, could be revolutionized by accepting the reality of higher human needs, including the impulse to self actualization and the love for the highest values.

Abraham Maslow

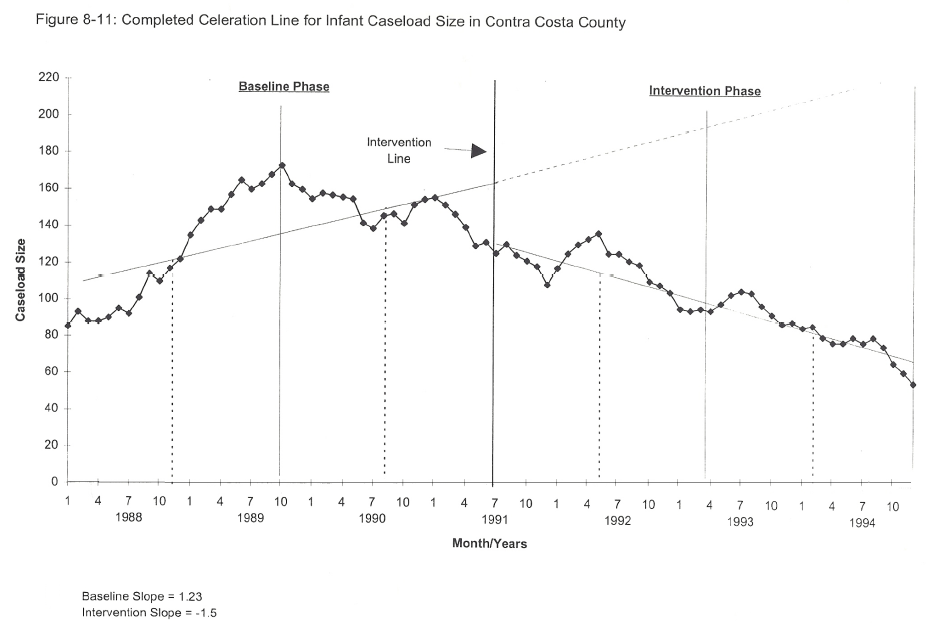

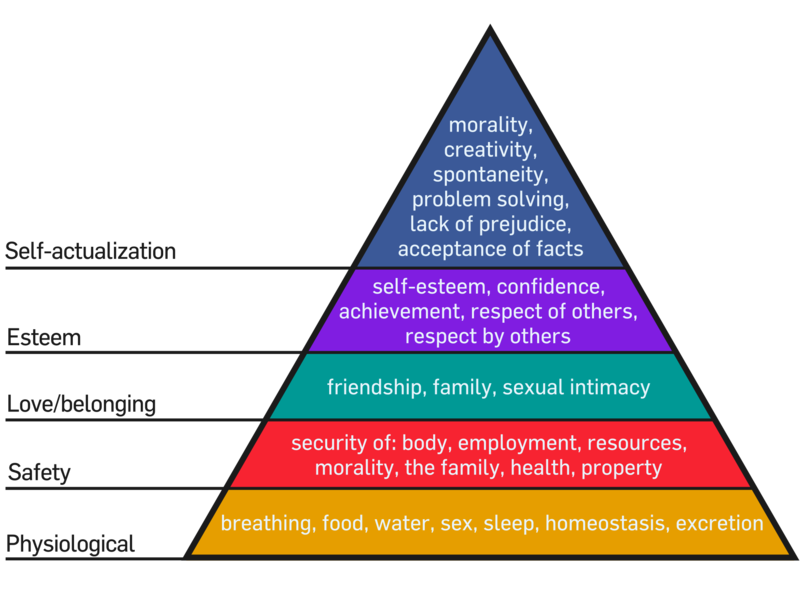

As presented in chapter 1, Abraham Maslow, a humanistic psychologist, proposed a hierarchy of human needs (1943) often portrayed as a pyramid (see Figure 4.7). Maslow’s pyramid integrates primary (biological) and secondary (psychological) needs into one overarching schema portraying the human condition. Basic physiological needs form the base of the pyramid, followed by safety and security, sense of belonging (i.e., love and interpersonal relationships), self-esteem (i.e. feeling of accomplishment), and self-actualization (fulfilling one’s personal goals and potential) at the pyramid’s peak.

Figure 4.5 Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs.

Maslow’s hierarchy is a perceptive and constructive schema for organizing and prioritizing aspects of the human condition. It provides a meaningful lens through which to view the differences between the adaptive needs of different cultures. According to Maslow, the objective of human adaptation is to rise through the pyramid ultimately achieving self-actualization.

Fulfilling Our Potential under Different Human Conditions

In order to demonstrate the extreme variability in human conditions, Maslow’s schema can serve as a basis for examining the differences between Stone-Age and technologically-advanced cultures. Obviously, far more time and effort must be dedicated by the Nukak than by us to satisfy the basic survival needs at the base of Maslow’s pyramid.

Self-actualization refers to the attainment of one’s personal goals and fulfillment of one’s potential. It is often assumed that self-actualization is achieved through creative and artistic endeavors. For the most part, the Nukak’s personal goals are addressed under survival and family needs. Fulfilling one’s potential requires time and opportunity, neither of which is in large supply for the Nukak. As we have seen, almost all of their days are taken up with activities related to survival. These include foraging, food preparation, tool making, moving, and building new shelters. Still, the Nukak manage to demonstrate such distinctly human acts of creativity as face and body painting and wearing jewelry. They fashion flutes on the flat side of long jaguar or deer bones with mouthpieces made of beeswax. Such flutes have important symbolic and ritual value among many tribes in the Amazon (Politis, 2007, 219). Body painting using plant dyes serves as a means of indicating one’s gender and band identity. Body painting is more extensive and elaborate in preparation for meetings and ceremonies (Politis, 2007, 83). It is thought that the paint may act as an insect repellent. Many of the Nukak adults and children of both genders wear necklaces fashioned of monkey-teeth.

Unlike the Nukak, we do not have to dedicate the majority of our time and effort to simply surviving until the next day. There is an ever-increasing variety of educational, career, and leisure-time possibilities. Still, many face obstacles in attaining their goals or realizing their potential. What are the prospects for self-actualization in the technologically enhanced world?

First, the importance of the “self” in “self-actualization” must be recognized. That is, “goals” and “one’s potential” are subjective and must be defined by each individual for her/himself. This thought is recognized in the most famous quote from The Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” Self-actualization and happiness are elusive concepts. Jonathan Haidt opens his book, The Happiness Hypothesis (2006), with the questions: “What should I do, how should I live, and whom should I become?” Despite all our technology, there are limitations to what we can do, how we can live, and who we can become. Unless an identical twin, each of us has our own genetic endowment resulting in differences in the ease of learning different behaviors. Try as we might, none of us is able to fly like Superman. Some of us find learning mathematics easier than learning to speak a foreign language whereas the reverse is true for others. Some of us live in environments that are supportive of our behaviors whereas others are discouraged or find it dangerous to behave in the same way. Some of us grow up in privilege and others face significant economic obstacles and barriers. Some of us have a smooth and direct educational and career path. Others of us follow a “long and winding road” in life.

No matter what our life circumstances or where we live on earth, a day lasts 24 hours. Our unique human conditions may be represented as pie charts in which the slices represent how we spend our time each day. Due to the conditions under which they live, more than half of a Nukak’s waking life is dedicated to survival needs. Relatively little time is left for addressing interpersonal and esteem-needs, let alone self-actualization. In comparison, college students in our technology-enhanced environments can dedicate much more of their waking time to these “higher” levels of Maslow’s pyramid of human needs.

Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs was used as an organizational schema to compare and contrast the human conditions of nomadic Stone-Age and technologically enhanced cultures. In the absence of food surpluses, life is a daily struggle to survive. Population densities and social networks are minimal. Advanced learning is unnecessary and there are few examples of artistic creativity.

Technology can free the human being from the struggle to meet basic physical needs. Much of childhood and adolescence can be dedicated to schooling. As an increasing percentage of the population acquires reading, writing, and quantitative skills, more individuals can contribute to a culture’s knowledge, technology, and creative arts. The social, vocational, and creative opportunities available to an individual are all influenced by the existing technologies. Life becomes adaptation to a human constructed world.

Self Actualization: The ultimate do-it-yourself project

Creation of a detailed personal pie chart involving recording and graphically portraying how you spend your time is a way to objectively describe who you are and who you want to become. This process can be diagnostic and prescriptive with respect to your achieving your self-actualization objectives. That is, realizing your potential can be considered an exercise in time management.

Whenever you undergo a transition in life, there is a change in how you must spend your time. This applies to when you start attending school, get a job, commit yourself to a significant other, have a child, advance in your career, and retire. Whew, that was fast! Let’s slow things down by concentrating on this particular and special time in your life. As a college student, you have committed yourself to a pie requiring specific slices. In addition to facing safety and survival needs, you must attend classes and prepare for exams. Otherwise you will be forced to “bake” a different pie!

The first step in creating your personal pie chart is to keep a diary of how you spend your time every day. Allowing for the fact that your schedule might not be representative at the beginning of the semester, you will probably need at least two weeks of data. It is probably possible to anticipate some of the pie “slices” (i.e., meaningful time blocks). For example, sleep will most likely constitute approximately one-third of your pie (i.e., 8 hours per day). Another slice could be allotted for “start-up” and “wind-down” (e.g., washing, brushing your teeth, etc.) each day, and another slice for meals. Time will be spent in class some days (another slice), and studying and working on assignments (another slice). Time will be spent socializing with friends and family. Many of my students use apps such as Screentime and Moment to monitor and limit time spent streaming, listening to music, social networking and playing video games. If you are employed, hours spent on the job and commuting (which can also apply to non-residential students) should be included.

If you are keeping a diary, add up the number of hours spent in different categories (slices) at the end of a representative week. The size of each slice (i.e., percentage of the pie) will be the total number of hours in a category divided by 168 (24 hours x 7 days). If you have trouble assigning some activities, it is fine to create a “miscellaneous” slice. In subsequent chapters, we will refer to the data you collect as you consider what constitutes self-actualization at this stage of your life (i.e., your “ideal” pie chart). This could require creating a different slice or even a separate pie (e.g., digital world or screen time).

The cell phone is becoming a very helpful self-actualization tool. If you own one, rather than keeping a diary, you could use one of the many convenient time-management apps for collecting and compiling the data for your pie chart. Some apps even create the pie chart for you. Other useful apps enable one to accurately determine sleep, nutritional, and exercise patterns. As we progress in the book, you will see how the science of psychology can provide scientifically-based strategies for modifying the slices of your pie in order to achieve your goals and dreams.

Figure Figure 3.6 The electromagnetic spectrum

Figure Figure 3.6 The electromagnetic spectrum