7.1: Defining Stock

7.1.1: Ownership Nature of Stock

The stock of a company represents the original capital paid into the business by its founders and can be purchased in the form of shares.

Learning Objective

Describe the ownership nature of stock

Key Points

- The stock (capital stock) of a company or business entity is equal to the original capital paid into the business by its founders.

- Stock serves as a security for creditors and investors in the business. While it may fluctuate in value, it is different from the assets and property of a business.

- A shareholder legally owns share of a stock in a public or private corporation, and has certain rights with regards to the company because of share ownership.

Key Terms

- Stock

-

The stock of a company represents the original capital paid into the business by its founders. It serves as a security for investors.

- shareholder

-

A shareholder legally owns at least one share of stock in a company and has rights with regards to the company because of this.

The Ownership Nature of Stock

The capital stock (or stock) of a business entity represents the original capital paid into or invested in the business by its founders. It serves as a security for the creditors of a business since it cannot be withdrawn to the detriment of the creditors. Stock is different from the property and assets of a business, both of which may fluctuate in quantity and value. Stock of a company is valued according to market demand and overall business health and this value will fluctuate over time. Ownership of stock represents a stake of ownership in the business entity. The stock is a security that represents equity in the company.

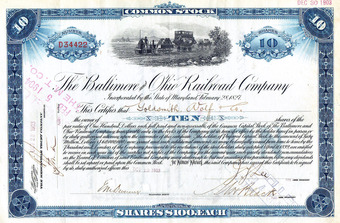

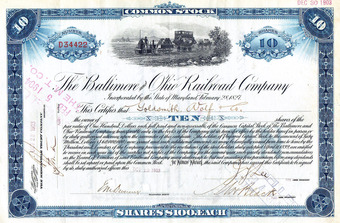

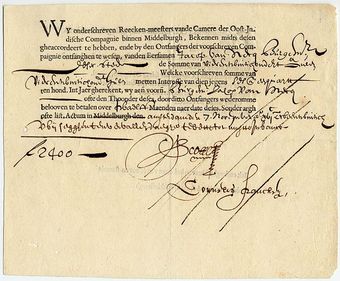

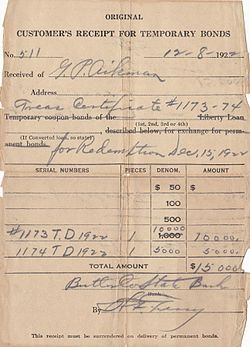

Ownership of shares is documented by issuance of a stock certificate . A stock certificate is a legal document that specifies the amount of shares owned by the shareholder, It also specifies other aspects of the shares like the par value or class of the shares. Other documents will specify what rights come with ownership of certain classes of stock.

1903 stock certificate of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Ownership of shares is documented by the issuance of a stock certificate and represents the shareholder’s rights with regards to the business entity.

Stakeholders

A shareholder or stockholder is an individual or institution (including a corporation) that legally owns a share of stock in a public or private corporation. Stockholders or shareholders are considered by some to be a subset of stakeholders, which may include anyone who has a direct or indirect interest in the business entity. For example, labor, suppliers, customers and the community are typically considered stakeholders because they contribute value and/or are impacted by the corporation.

7.1.2: Control and Preemption

Shareholders have the right of preemption, meaning they have the first chance at buying newly issued shares of stock before the general public.

Learning Objective

Explain a shareholders’ control and preemption rights

Key Points

- Shareholders gain certain rights with regards to a business entity when purchasing stock. These include being able to sell shares, voting rights and dividends.

- Shareholders have the right of preemption, meaning they have the first chance at buying newly issued shares of stock before the general public.

- Even if shareholders do have the option of using their preemptive right, they do not have to exercise it.

Key Terms

- preemptive right

-

a contractual ability to acquire certain property newly coming into existence before it can be offered to any other person or entity

- Preemption

-

The right of a shareholder to purchase newly issued shares of a business entity before they are available to the general public so as to protect individual ownership from dilution.

Rights of Stockholders

A shareholder or stockholder is an individual or institution (including a corporation) that legally owns a share of stock in a public or private corporation. Stockholders are granted special privileges depending on the class of stock. These rights may include:

- The right to sell shares

- The right to vote on directors nominated by the board,

- The right to nominate directors (although this is very difficult in practice because of minority protections) and propose shareholder resolutions

- The right to dividends if they are declared

- The right to purchase new shares issued by the company

- The right to what assets remain after a liquidation

Owners of common and preferred stock generally have to wait until debt-holders receive assets after bankruptcy to see any assets after liquidation.

Control and Preemption

Control and preemption are particular stockholder rights.

A preemption right, or right of preemption, is a contractual right to acquire certain property coming into existence before it can be offered to any other person or entity. This right is frequently applied for shareholders of a business entity as they are usually offered the first chance to buy newly issued shares of stock before it becomes available to the general public. While shareholders are offered the option of early purchase, they do not necessarily have to take it. The incentive to exercise this option is based on the desire to protect individual ownership or stake in a company from dilution. The conditions of preemptive rights will vary from company to company and share type to share type.

Shareholder Meeting

This scene from “The Office” humorously illustrates a shareholder meeting, where the shareholder can exercise their right to vote on company issues or question company directors.

7.2: Types of Stock

7.2.1: Common Stock

Common stock is a form of ownership and equity, different from preferred stock, that still earns rights of ownership for its shareholders.

Learning Objective

Describe what benefits a common shareholder receives

Key Points

- Common stock is a form of equity ownership. It is a type of security that is also known as a voting share or an ordinary share.

- Common stock shareholders will not receive assets after bankruptcy unless the bondholders, other creditors, and preferred shareholders are paid first. Common shareholders also do not get dividends unless preferred shareholders receive them first.

- Common shareholders do receive voting rights. Some shareholders may also be able to exercise preemptive rights.

Key Terms

- Common stock

-

Common stock is a form of equity and type of security. Common stock shareholders are at the bottom of the line when it comes to dividends and receiving compensation in the case of bankruptcy.

- equity

-

The residual claim or interest to investors in assets after all liabilities are paid. If liability exceeds assets, negative equity exists and can be purchased through stock.

- dividend

-

Dividends are payments made by a corporation to its shareholder members.

Common stock is a form of corporate equity ownership, which is a type of security . The terms “voting share” or “ordinary share” are also used in other parts of the world. “Common stock” is used primarily in the United States. It is called “common” to distinguish it from preferred stock. If both types of stock exist, common stock holders cannot be paid dividends until all preferred stock dividends (including payments in arrears) are paid in full. Should bankruptcy occur, common stock shareholders receive any remaining funds after the bondholders, creditors (including employees), and preferred stockholders. Such shareholders usually receive nothing in the case of company liquidation.

New York Stock Exchange

Stocks can be bought and sold on exchanges, like the New York Stock Exchange shown above.

While Common stockholders are generally last in line among other creditors to receive assets should the business in question go bankrupt, common shares do tend to perform better than preferred shares over time. Also, Common stock usually carries the right to vote on certain matters. These matters include but are not limited to deciding for who gets to sit on the board of directors of the company. However, a company can have both a “voting” and “non-voting” class of common stock. Common shareholders do not get guaranteed dividends, so their returns can be uncertain. It must be remembered that Preferred stock generally does not carry voting rights.

Holders of common stock are able to influence the corporation through votes on establishing corporate objectives and policy, stock splits, and electing the company’s board of directors. Some holders of common stock also receive preemptive rights, which enable them to retain their proportional ownership in a company should it issue another stock offering.

7.2.2: Preferred Stock

Preferred stock usually carries no voting rights, but may carry a dividend, have priority over common stock upon liquidation and/or have other benefits.

Learning Objective

Describe the rights and obligations of preferred stock

Key Points

- Preferred Stock is a security which has characteristics of both equity and debt securities.

- Preferred Stock shareholders have rights to dividends and assets (in the case of bankruptcy) before Common Stock shareholders.

- Preferred stockholders have a number of rights which will vary based on the business entity, but generally do not carry voting rights.

Key Terms

- bond

-

A bond is an instrument of indebtness of the bond issuers toward the bond holders.

- Preferred Stock

-

Preferred stock is an equity security that has the properties of both an equity and debt instrument and is higher ranking than common stock.

Preferred stock (also called preferred shares, preference shares or simply preferreds) is an equity security with properties of both an equity and a debt instrument , and is generally considered a hybrid instrument. It is senior (i.e. higher ranking) to common stock, but subordinate to bonds in terms of claim (or rights to their share of the assets of the company). In other words, in the case of liquidation or bankruptcy, preferred stock will have claim to assets before common stock, but after corporate bonds or other debt instruments.

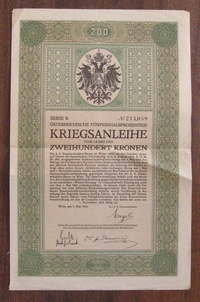

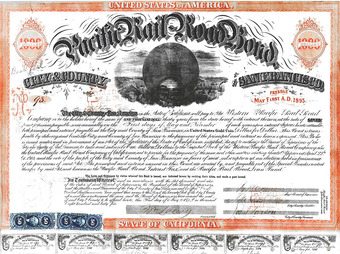

Bond

Preferred Stocks are considered a hybrid security with properties of both stocks and bonds, but are subordinate to bonds when it comes to rights of claim to company assets.

Preferred stock usually carries no voting rights, but may carry a dividend and may have priority over common stock in the payment of dividends and upon liquidation. The specific terms of owning preferred stock are specified in a certificate of designation. The features and rights which are generally associated with preferred stock are as follows:

- Preference in dividends

- Preference in assets in the event of liquidation

- Convertibility to common stock

- Callability, at the option of the corporation

- Nonvoting rights.

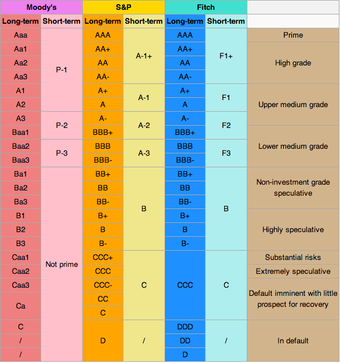

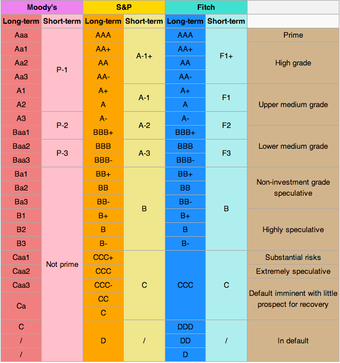

Similar to bonds, preferred stocks are rated by the major credit-rating companies. The rating for preferreds is generally lower, since preferred dividends do not carry the same guarantees as interest payments from bonds, and they are junior to all creditors.

Details with regards to the rights associated with preferred stock will vary with the business entity that issues the shares, and preferred stock can come in a number of different classes. Some examples are prior preferred stock (highest priority), preference preferred stock, convertible preferred stock (exchangeable for common stock), cumulative preferred stock, exchangeable preferred stock, participating preferred stock, putable preferred stock, monthly income preferred stock, and non-cumulative preferred stock.

7.3: Rules and Rights of Common and Preferred Stock

7.3.1: Claim to Income

In the cases of bankruptcy and dividend distribution, preferred stock shareholders will receive assets before common stock shareholders.

Learning Objective

Describe the rights preferred stock has to a company’s income

Key Points

- Common stock and preferred stock are both forms of equity ownership but carry different rights and claims to income.

- Preferred stock shareholders will have claim to assets over common stock shareholders in the case of company liquidation.

- Preferred stock also has first right to dividends.

Key Terms

- Common stock

-

Common stock is a form of equity and type of security. Common stock shareholders are at the bottom of the line when it comes to dividends and receiving compensation in the case of bankruptcy.

- Preferred Stock

-

Preferred stock is an equity security that has the properties of both an equity and debt instrument and is higher ranking than common stock.

Preferred and common stock have varying claims to income which will change from one equity issuer to another. In general, preferred stock will be given some preference in assets to common assets in the case of company liquidation, but both will fall behind bondholders when asset distribution takes place. In the event of bankruptcy, common stock investors receive any remaining funds after bondholders, creditors (including employees), and preferred stock holders are paid. As such, these investors often receive nothing after a bankruptcy. Preferred stock also has the first right to receive dividends. In general, common stock shareholders will not receive dividends until it is paid out to preferred shareholders. Access to dividends and other rights vary from firm to firm.

1903 stock certificate of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

Preferred and common stock both carry rights of ownership, but represent different classes of equity ownership.

Preferred stock may or may not have a fixed liquidation value (or par value) associated with it. This represents the amount of capital that was contributed to the corporation when the shares were first issued. Preferred stock has a claim on liquidation proceeds of a stock corporation equal to its par (or liquidation) value, unless otherwise negotiated. This claim is senior to that of common stock, which has only a residual claim.

Both types of stock can have a claim to income in the form of capital appreciation as well. As company value increases based on market determinants, the value of equity held in this company also will increase. This translates to a return on investment to shareholders. This will be different to common stock shareholders and preferred stock shareholders because of the different prices and rewards based on holding these different kinds of shares. In turn, should market forces decrease, the value of equity held will decrease as well, reflecting a loss on investment and, therefore, a decrease on the value of any claims to income for shareholders.

7.3.2: Voting Right

Common stock generally carries voting rights, while preferred stock does not; however, this will vary from company to company.

Learning Objective

Summarize the voting rights associated with common and preferred stock

Key Points

- Common stock shareholders can generally vote on issues, such as members of the board of directors, stock splits, and the establishment of corporate objectives and policy.

- While having superior rights to dividends and assets over common stock, generally preferred stock does not carry voting rights.

- Many of the voting rights of a shareholder can be exercised at annual general body meetings of companies. An annual general meeting is a meeting that official bodies, and associations involving the general public, are often required by law to hold.

Key Terms

- Voting rights

-

Rights which are generally associated with common stock shareholders in regards to business entity matters ( such as electing the board of directors or establishing corporate policy)

- Preferred Stock

-

Preferred stock is an equity security that has the properties of both an equity and debt instrument and is higher ranking than common stock.

- Common stock

-

Common stock is a form of equity and type of security. Common stock shareholders are at the bottom of the line when it comes to dividends and receiving compensation in the case of bankruptcy.

Voting Rights

Common stock can also be referred to as a “voting share. ” Common stock usually carries with it the right to vote on business entity matters, such as electing the board of directors, establishing corporate objectives and policy, and stock splits. However, common stock can be broken into voting and non-voting classes. While having superior rights to dividends and assets over common stock, generally preferred stock does not carry voting rights.

The matters that a stockholder gets to vote on vary from company to company. In many cases, the shareholder will be able to vote for members of a company board of directors and, in general, each share gets a vote as opposed to each shareholder. Therefore, a single investor who owns 300 shares will have more say in a voting matter than a single shareholder that owns 30.

Exercising Voting Rights

Many of the voting rights of a shareholder can be exercised at annual general body meetings of companies. An annual general meeting is a meeting that official bodies and associations involving the general public (including companies with shareholders) are often required by law (or the constitution, charter, by-laws, etc., governing the body) to hold. An AGM is held every year to elect the board of directors and inform their members of previous and future activities. It is an opportunity for the shareholders and partners to receive copies of the company’s accounts, as well as reviewing fiscal information for the past year and asking any questions regarding the directions the business will take in the future. Shareholders also have the option to mail their votes in if they cannot attend the shareholder meetings. In 2007, the Securities and Exchange Commission voted to require all public companies to make their annual meeting materials available online. Shareholders with the right to vote will have numerous options in how to make their voice heard with regards to voting matters should they choose to.

Shareholder Meeting

This scene from “The Office” humorously illustrates a shareholder meeting, where the shareholder can exercise their right to vote on company issues or question company directors.

7.3.3: Purchasing New Shares

New shares can be purchased on exchanges and current shareholders will usually have preemptive rights to newly issued shares.

Learning Objective

Discuss the process and implication of purchasing new shares by a shareholder that already holds shares in a company

Key Points

- New share purchase is an important indicator of current shareholder belief in the health of the company and long term prospects for growth.

- Current Shareholders will often have preemptive rights that give them the right to purchase newly issued company shares before they go on sale to the general public.

- New shares can be purchased on exchanges, which offer a platform for the financial marketplace.

Key Terms

- Stock Exchange

-

A form of exchange that provides services for stock brokers and traders to trade stocks, bonds and other securities.

- Preemption

-

The right of a shareholder to purchase newly issued shares of a business entity before they are available to the general public so as to protect individual ownership from dilution.

New share purchases are an important action by share shareholders, since it requires a further investment in a business entity and is a reflection of a shareholder’s decision to maintain an ownership position in a company, or a potential investor’s belief that purchasing equity in a company will be an investment that grows in value.

Current shareholders may have preemptive rights over new shares offered by the company. In practice, the most common form of preemption right is the right of existing shareholders to acquire new shares issued by a company in a rights issue, a usually but not always public offering. In this context, the pre-emptive right is also called “subscription right” or “subscription privilege. ” This is the right, but not the obligation, of existing shareholders to buy the new shares before they are offered to the public. In this way, existing shareholders can maintain their proportional ownership of the company, preventing stock dilution.

New shares may be purchased over the same exchange mechanisms that previous stock was acquired. A stock exchange is a form of exchange which provides services for stock brokers and traders to trade stocks, bonds, and other securities. Stock exchanges also provide facilities for issue and redemption of securities and other financial instruments, and capital events, including the payment of income and dividends. The initial offering of stocks and bonds to investors is by definition done in the primary market and subsequent trading is done in the secondary market. A stock exchange is often the most important component of a stock market. Supply and demand in stock markets are driven by various factors that, as in all free markets, affect the price of stocks.

Exchanges

New shares can be traded on exchanges such as the Nasdaq, but will usually be offered to current shareholders before being put on sale to the general public.

7.3.4: Preferred Stock Rules and Rights

Preferred stock can include rights such as preemption, convertibility, callability, and dividend and liquidation preference.

Learning Objective

List the rights that preferred stock generally has

Key Points

- Preferred stock generally does not carry voting rights, but this may vary from company to company.

- Preferred stock can gain cumulative dividends, convertibility to common stock, and callability.

- The rights that come with ownership of preferred stock are detailed in a “Certificate of Designation”.

Key Terms

- liquidation

-

liquidation is the process by which a company (or part of a company) is brought to an end, and the assets and property of the company redistributed

- Preferred Stock

-

Preferred stock is an equity security that has the properties of both an equity and debt instrument and is higher ranking than common stock.

Preferred stock usually carries no voting rights, but may carry a dividend and may have priority over common stock in the payment of dividends and upon liquidation. Terms of the preferred stock are stated in a “Certificate of Designation. “

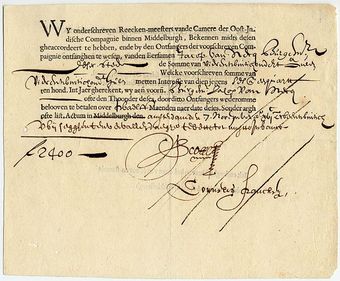

VOC stock

Preferred stock is a security ( a little more modern that this stock from the VOC or Dutch East India Company) that carries certain rights which designate it from common stock or debt.

Preferred stock is a special class of shares that may have any combination of features not possessed by common stock. The following features are usually associated with preferred stock: Preference in dividends preference in assets, in the event of liquidation, convertibility to common stock, callability, and at the option of the corporation. Some preferred shares have special voting rights to approve extraordinary events (such as the issuance of new shares or approval of the acquisition of a company) or to elect directors, but, once again, most preferred shares have no voting rights associated with them. Some preferred shares gain voting rights when the preferred dividends are in arrears for a substantial time.

Preferred stock may or may not have a fixed liquidation value (or par value) associated with it. This represents the amount of capital which was contributed to the corporation when the shares were first issued. Preferred stock has a claim on liquidation proceeds of a stock corporation equal to its par (or liquidation) value, unless otherwise negotiated. This claim is senior to that of common stock, which has only a residual claim.Almost all preferred shares have a negotiated, fixed-dividend amount. The dividend is usually specified as a percentage of the par value, or as a fixed amount. Sometimes, dividends on preferred shares may be negotiated as floating; they may change according to a benchmark interest-rate index. Preferred stock may also have rights to cumulative dividends.

7.3.5: Provisions of Preferred Stock

Preferred shares have numerous rights which can be attached to them, such as cumulative dividends, convertibility, and participation.

Learning Objective

Describe in detail the different types of provisions for preferred stock

Key Points

- If a preferred share has cumulative dividends, then it contains the provision that should a company fail to pay out dividends at any time at the stated rate, then the issuer will have to make up for it as time goes on.

- Convertible preferred stock can be exchanged for a predetermined number of company common stock shares.

- Often times companies will keep the right to call or buy back preferred shares at a predetermined price.

- Participating preferred issues offer holders the opportunity to receive extra dividends if the company achieves predetermined financial goals.

- Sometimes, dividends on preferred shares may be negotiated as floating; they may change according to a benchmark interest-rate index.

Key Terms

- Callable shares

-

Shares which can be bought back by the issuer at a predetermined price.

- Convertible preferred stock

-

Convertible preferred stock can be exchanged for a predetermined number of company common stock shares.

- Cumulative Dividends

-

Condition where owners of certain shares will receive accumulated dividends in the case a company cannot pay out dividends at the stated rate at the stated time.

Preferred stock may be entitled to numerous rights, depending on what is designated by the issuer. One of these rights may be the right to cumulative dividends. Preferred stock shareholders already have rights to dividends before common stock shareholders, but cumulative preferred shares contain the provision that should a company fail to pay out dividends at any time at the stated rate, then the issuer will have to make up for it as time goes on.

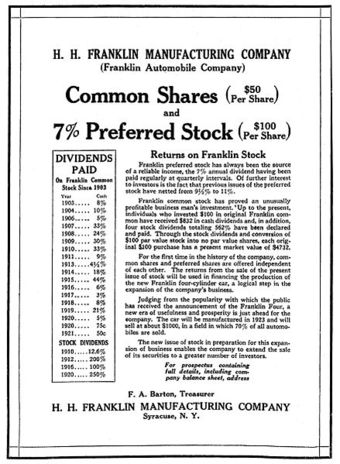

Historical dividend information for Franklin Automobile Company

Dividends are one of the privileges of stock ownership, and preferred shares get more rights to them than common shares do.

Convertible preferred stock can be exchanged for a predetermined number of company common stock shares. Generally, this can occur at the discretion of the investor, and he or she may pick any time to do so and, therefore, take advantage of fluctuations in the price of common stock. Once converted, the common stock cannot be converted back to preferred status.

Often times companies will keep the right to call or buy back preferred shares at a predetermined price. These shares are callable shares.

There is a class of preferred shares known as “participating preferred stock. ” These preferred issues offer holders the opportunity to receive extra dividends if the company achieves predetermined financial goals. Investors who purchased these stocks receive their regular dividend regardless of company performance (assuming the company does well enough to make its annual dividend payments). If the company achieves predetermined sales, earnings, or profitability goals, the investors receive an additional dividend.

Almost all preferred shares have a negotiated, fixed-dividend amount. The dividend is usually specified as a percentage of the par value, or as a fixed amount. Sometimes, dividends on preferred shares may be negotiated as floating; they may change according to a benchmark interest-rate index or floating rate. An example of this would be tying the dividend rate to LIBOR.

7.3.6: Comparing Common Stock, Preferred Stock, and Debt

Common stock, preferred stock, and debt are all securities that a company may offer; each of these securities carries different rights.

Learning Objective

Differentiate between the rights of common shareholders, preferred shareholders, and bond holders

Key Points

- Common stock and preferred stock fall behind debt holders as creditors that would receive assets in the case of company liquidation.

- Common stock and preferred stock are both types of equity ownership. They receive rights of ownership in the company, such as voting and dividends.

- Debt holders often receive a bond for lending and while this does not give the ownership rights of being a stockholder, it does create a superior claim to a company’s assets in the case of liquidation.

Key Terms

- Common stock

-

Common stock is a form of corporate equity ownership, a type of security.

- bond

-

A bond is an instrument of indebtness of the bond issuers toward the bond holders.

- Preferred Stock

-

Preferred stock is an equity security that has the properties of both an equity and debt instrument and is higher ranking than common stock.

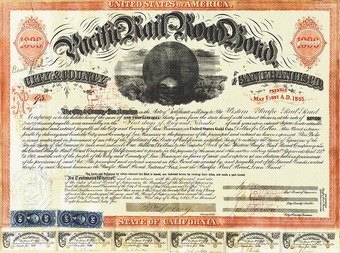

Equity

Common Stock and Preferred Stock are both methods of purchasing equity in a business entity.

Common stock generally carries voting rights along with it, while preferred shares generally do not.

Preferred shares act like a hybrid security, in between common stock and holding debt. Preferred stock can (depending on the issue) be converted to common stock and have access to accumulated dividends and multiple other rights. Preferred stock also has access to dividends and assets in the case of liquidation before common stock does.

However, both common and preferred stock fall behind debt holders when it comes to claims to assets of a business entity should bankruptcy occur. Common shareholders often do not receive any assets after bankruptcy as a result of this principle. However, common stock shareholders can theoretically use their votes to affect company decision making and direction in a way they believe will help the company avoid liquidation in the first place.

Debt

Debt can be “purchased” from a company in the form of a bond.

A bond from the Dutch East India Company

A bond is a financial security that represents a promise by a company or government to repay a certain amount, with interest, to the bondholder.

In finance, a bond is an instrument of indebtedness of the bond issuer to the holders. It is a debt security, under which the issuer owes the holders a debt and, depending on the terms of the bond, is obliged to pay them interest and/or to repay the principal at a later date, termed the maturity. Therefore, a bond is a form of loan or IOU: the holder of the bond is the lender (creditor), the issuer of the bond is the borrower (debtor), and the coupon is the interest. Bonds provide the borrower with external funds to finance long-term investments, or, in the case of government bonds, to finance current expenditure.

Bonds and stocks are both securities, but the major difference between the two is that (capital) stockholders have an equity stake in the company (i.e., they are owners), whereas, bondholders have a creditor stake in the company (i.e., they are lenders). Another difference is that bonds usually have a defined term, or maturity, after which the bond is redeemed, whereas stocks may be outstanding indefinitely.

7.4: Stock Markets

7.4.1: Market Actors

Market actors include individual retail investors, mutual funds, banks, insurance companies, hedge funds, and corporations.

Learning Objective

Identify the different actors that participate in a stock market

Key Points

- Pension funds are important shareholders of listed and private companies.

- Insurance companies are generally classified as either mutual or proprietary companies.

- A mutual fund is a type of professionally-managed collective investment vehicle that pools money from many investors to purchase securities.

- An index fund or index tracker is a collective investment scheme (usually a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund) that aims to replicate the movements of an index of a specific financial market, or a set of rules of ownership that are held constant, regardless of market conditions.

- An exchange-traded fund (ETF) is an investment fund traded on stock exchanges, much like stocks.

- A hedge fund is an fund that can undertake a wider range of investment and trading activities than other funds. It is generally only open to certain types of investors specified by regulators.

Key Terms

- open-end

-

An open-end(ed) fund is a collective investment scheme which can issue and redeem shares at any time.

- closed-end

-

Closed-end funds (or closed-ended funds) are mutual funds with a fixed number of shares (or units). Unlike open-end funds, new shares/units are not created by managers, to meet demand from investors, but the shares can only be purchased (and sold) in the market.

The individual actors in the financial markets can be broken down into three main categories: investors, intermediaries, and issuers. Specifically, market actors include individual retail investors, institutional investors such as mutual funds, banks, insurance companies and hedge funds, and also publicly traded corporations trading in their own shares. The value of a stock is derived from buying and selling decisions of these actors. Some studies have suggested that institutional investors and corporations trading in their own shares generally receive higher risk-adjusted returns than retail investors .

Stock Market

Different kinds of investors are active in stock market.

Investors

An investor is someone who allocates capital with the expectation of a financial return. The types of investments include, — equity, debt securities, real estate, currency, commodity, derivatives such as put and call options, etc. A few decades ago, worldwide, buyers and sellers were individual investors, such as wealthy businessmen, usually with long family histories to particular corporations. Over time, markets have become more “institutionalized. ” Buyers and sellers are largely institutions. Investors can include: pension funds, insurance companies, mutual funds, index funds, exchange-traded funds, and hedge funds.

Issuers

The issuer is a legal entity that develops, registers, and sells securities for the purpose of financing its operations. Issuers may be domestic or foreign governments, corporations, or investment trusts.

Intermediaries

Financial institutions (intermediaries) perform the vital role of bringing together those economic agents with surplus funds who want to lend, with those with a shortage of funds who want to borrow. The classic example of a financial intermediary is a bank that consolidates bank deposits and uses the funds to transform them into bank loans. Other classes of intermediaries include: credit unions, financial advisers or brokers, collective investment schemes, and pension funds.

Pension funds

A pension fund is any plan, fund, or scheme that provides retirement income.

Pension funds are important shareholders of listed and private companies. They are especially important to the stock market where large institutional investors dominate. The largest 300 pension funds collectively hold about $6 trillion in assets. In January 2008, The Economist reported that Morgan Stanley estimates that pension funds worldwide hold over $20 trillion in assets, the largest for any category of investor ahead of mutual funds, insurance companies, currency reserves, sovereign wealth funds, hedge funds, or private equity.

Insurance companies

Insurance companies are generally classified as either mutual or proprietary companies. Mutual companies are owned by the policyholders, while shareholders (who may or may not own policies) own proprietary insurance companies.

Mutual funds

A mutual fund is a type of professionally-managed collective investment vehicle that pools money from many investors to purchase securities. While there is no legal definition of mutual fund, the term is most commonly applied only to those collective investment vehicles that are regulated, available to the general public, and open-ended in nature. Hedge funds are not considered a type of mutual fund.

There are three types of U.S. mutual funds: open-end, unit investment trust, and closed-end. The most common type, the open-end mutual fund, must be willing to buy back its shares from its investors at the end of every business day. Exchange-traded funds are open-end funds or unit investment trusts that trade on an exchange. Open-end funds are most common, but exchange-traded funds have been gaining in popularity.

Index fund

An index fund or index tracker is a collective investment scheme (usually a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund) that aims to replicate the movements of an index of a specific financial market, or a set of rules of ownership that are held constant, regardless of market conditions. As of 2007, index funds made up over 11% of equity mutual fund assets in the United States.

Exchange-traded fund (ETF)

An exchange-traded fund (ETF) is an investment fund traded on stock exchanges, much like stocks. An ETF holds assets such as stocks, commodities, or bonds, and trades close to its net asset value over the course of the trading day. Most ETFs track an index, such as a stock index or bond index. ETFs may be attractive as investments because of their low costs, tax efficiency, and stock-like features. ETFs are the most popular type of exchange-traded product.

Hedge fund

A hedge fund is an fund that can undertake a wider range of investment and trading activities than other funds. It is generally only open to certain types of investors specified by regulators. These investors are typically institutions, such as pension funds, university endowments and foundations, or high-net-worth individuals, who are considered to have the knowledge or resources to understand the nature of the funds. As a class, hedge funds invest in a diverse range of assets, but they most commonly trade liquid securities on public markets. They also employ a wide variety of investment strategies, and make use of techniques such as short selling and leverage.

7.4.2: NYSE

The New York Stock Exchange is the world’s largest stock exchange by market capitalization at $14.242 trillion as of December 2011.

Learning Objective

Distinguish the New York Stock Exchange from other stock exchanges

Key Points

- The origin of the NYSE can be traced to May 17, 1792, when the Buttonwood Agreement was signed by 24 stockbrokers outside of 68 Wall Street in New York under a buttonwood tree on Wall Street.

- The New York Stock Exchange (sometimes referred to as “the Big Board”) provides a means for buyers and sellers to trade shares of stock in companies registered for public trading.

- The New York Stock Exchange is open for trading Monday through Friday from 9:30 am to 4:00 pm ET, with the exception of holidays declared by the NYSE in advance.

- Traders can gather around the appropriate post. There, a specialist broker acts as an auctioneer in an open outcry auction market environment to bring buyers and sellers together and to manage the actual auction.

- To be listed on the New York Stock Exchange, a company must have issued at least a million shares of stock worth $100 million and must have earned more than $10 million over the last three years.

Key Terms

- Dutch auction

-

an event to buy or sell that starts at a high price that is gradually reduced by the auctioneer until someone is willing to buy

- secondary market

-

The financial market in which previously issued financial instruments such as stock, bonds, options, and futures are bought and sold.

- NASDAQ

-

The National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations; this is an electronic stock market.

New York Stock Exchange

The New York Stock Exchange, commonly referred to as the NYSE, is a stock exchange, or a secondary market. With primary issuances of securities or financial instruments, or the primary market, investors purchase these securities directly from issuers such as corporations issuing shares in an IPO or private placement, or directly from the federal government in the case of treasuries.

After the initial issuance, investors can purchase from other investors in secondary markets like the NYSE. If an investor wished to buy a stock from Apple, for example, the actual company is not directly involved. Secondary markets can be further subdivided into auction or dealer markets, typified by the mode of transactions. The NYSE is an auction market. Buyers and sellers meet at a physical location (in this case, Wall Street) and announce their bid or ask prices.

At the NYSE, traders gather around a specialist broker, who acts as an auctioneer in an open outcry auction market environment to bring buyers and sellers together and to manage the actual auction. The auction market format aims to bring together the parties with mutually agreeing prices in an efficient manner. The auction process moved toward automation in 1995 through the use of wireless hand held computers (HHC). The system enabled traders to receive and execute orders electronically via wireless transmission .

NYSE Trading Floor

Buyers and sellers meet and engage in face-to-face transactions at the NYSE, which is an auction-style secondary market.

The NYSE is by far the world’s largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed companies at $14.242 trillion as of December 2011, and most of the largest US companies are listed on the NYSE. The NYSE’s biggest competitor is NASDAQ; both are major secondary markets vying for large and profitable companies to list on their exchange.

Secondary markets like the NYSE serve a vital function as a setting where companies can raise capital for expansion through selling shares to the investing public. They also gain advertising and a boost in prestige, which likely increases their stock value. To be able to trade a security on the NYSE, it must be listed. To be listed on the New York Stock Exchange, a company must have issued at least a million shares of stock worth $100 million and must have earned more than $10 million over the last three years. They must also disclose certain information to the exchange, providing a measure of transparency that prevents insider manipulation of the stock prices.

7.4.3: NASDAQ

The NASDAQ is an American dealer-based stock market in which the dealers sell electronically to investors or firms.

Learning Objective

Distinguish the NASDAQ from other stock exchanges

Key Points

- NASDAQ was founded in 1971 by the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), who divested themselves of it in a series of sales in 2000 and 2001.

- NASDAQ quotes are available at three levels: Level 1 shows the highest bid and lowest offer; Level 2 shows all public quotes of market makers; Level 3 is used by the market makers and allows them to enter their quotes and execute orders.

- NASDAQ has a pre-market session from 7:00am to 9:30am, a normal trading session from 9:30am to 4:00pm, and a post-market session from 4:00pm to 8:00pm (all times in ET).

- Three market tiers are NASDAQ Capital Market – Small Cap, NASDAQ Global Market – Mid Cap, NASDAQ Global Select Market – Large Cap.

Key Term

- FINRA

-

In the United States, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, Inc., or FINRA, is a private corporation that acts as a self-regulatory organization (SRO). FINRA is the successor to the National Association of Securities Dealers, Inc. (NASD). Though sometimes mistaken for a government agency, it is a non-governmental organization that performs financial regulation of member brokerage firms and exchange markets. The government organization which acts as the ultimate regulator of the securities industry, including FINRA, is the Securities and Exchange Commission.

NASDAQ Stock Market

The NASDAQ Stock Market, also known simply as the NASDAQ, is an American stock exchange. “NASDAQ” originally stood for “National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations. ” It is one of the largest stock exchanges in the world along with the New York Stock Exchange.

NASDAQ

NASDAQ is the second-largest stock exchange market in the world, as of 2012.

The NASDAQ is a dealer-based market in which stock dealers sell directly to investors or firms electronically via phone or Internet. The New York Stock Exchange conducts its trading in person.

History

NASDAQ was founded in 1971 by the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), who divested themselves of it in a series of sales in 2000 and 2001. It is owned and operated by the NASDAQ OMX Group and regulated by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), the successor to the NASD.

When the NASDAQ stock exchange began trading on February 8, 1971, it was the world’s first electronic stock market. At first, it was merely a computer bulletin board system and did not actually connect buyers and sellers. The NASDAQ helped lower the spread (the difference between the bid price and the ask price of the stock), but paradoxically was unpopular among brokerages because they made much of their money on the spread.

Firms including Microsoft began doing business through NASDAQ early in their history, and remained with this exchange as the technology industry boomed. NASDAQ became known for its concentration of tech and high-growth firms, making it the primary tech market and an indicator for industry trends.

Indices

A stock index or stock market index is a method of measuring the value of a section of the stock market. It is computed from the prices of selected stocks, which vary depending on the index. Investors and financial managers can use it as a “snapshot” to describe the market conditions, and also as a tool to compare the return on specific investments. NASDAQ’s major indices include:

- NASDAQ-100

- NASDAQ Bank

- NASDAQ Biotechnology Index

- NASDAQ Transportation Index

- NASDAQ Composite

The NASDAQ Composite is often referred to as the NASDAQ. It is calculated from weighting common stocks and similar securities listed on the NASDAQ stock market. Thus “NASDAQ” can mean two things: either the stock exchange itself, or the index.

7.4.4: Market Reporting

Market indices provide valuable information for stock valuation.

Learning Objective

Explain how a market index works and its purpose

Key Points

- The is a tool used by investors and financial managers to describe the market and to compare the return on specific investments.

- An index is a mathematical construct, so it may not be invested in directly.

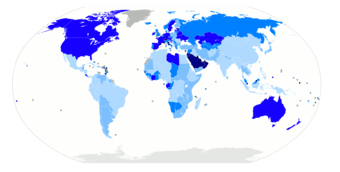

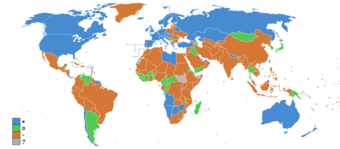

- A ‘world’ or ‘global’ stock market index includes (typically large) companies without regard for where they are domiciled or traded.

- A ‘national’ index represents the performance of the stock market of a given nation—and by proxy, reflects investor sentiment on the state of its economy.

- Stock market indices provide invaluable information for investors and accountants.

Key Terms

- market capitalization

-

The total market value of the equity in a publicly traded entity.

- weighted average

-

An arithmetic mean of values biased according to agreed weightings.

- Common stock

-

Shares of an ownership interest in the equity of a corporation or other entity with limited liability. Holders of this type of stock are entitled to dividends. Importantly, the financial rights for holders of this type of stock are junior to preferred stock and liabilities.

Market Reporting

A stock index or stock market index is a method of measuring the value of a section of the stock market. It is computed from the prices of selected stocks (sometimes a weighted average). It is a tool used by investors and financial managers to describe the market and to compare the return on specific investments.

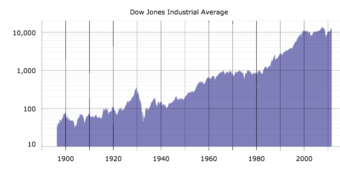

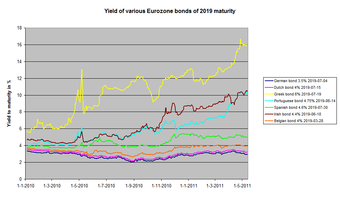

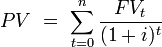

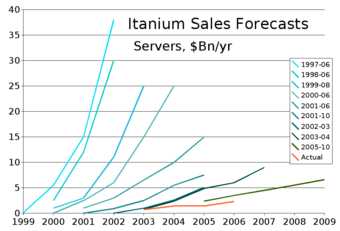

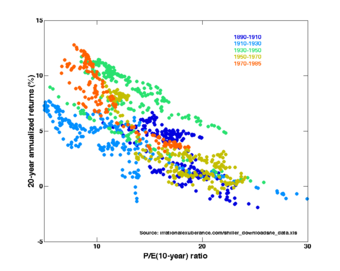

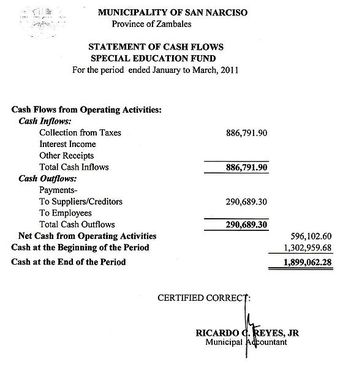

Historical Graph of the Dow Jones Industrial Average

This graph shows the general increase in the DJIA over the last century. Particularly notable is the growth from around 1,000 points in the late 1980s to around 10,000 points in 2005.

An index is a mathematical construct, so it may not be invested in directly. Many mutual funds and exchange-traded funds attempt to “track” an index. The funds that do may not be judged against those that do.

Stock market indices may be classed in many ways. A ‘world’ or ‘global’ stock market index includes (typically large) companies without regard for where they are domiciled or traded. Two examples are MSCI World and S&P Global 100.

A ‘national’ index represents the performance of the stock market of a given nation—and by proxy, reflects investor sentiment on the state of its economy. The most regularly quoted market indices are national indices composed of the stocks of large companies listed on a nation’s largest stock exchanges, such as the American S&P 500, the Japanese Nikkei 225, the Brazilian Ibovespa, the Russian RTSI, the Indian SENSEX, and the British FTSE 100.

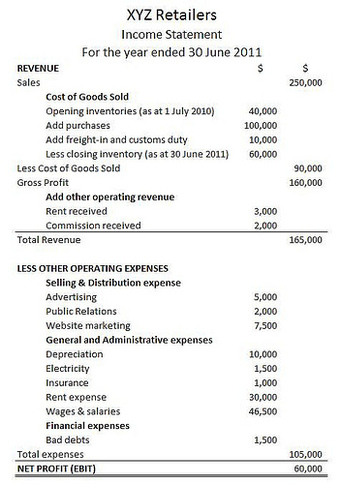

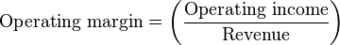

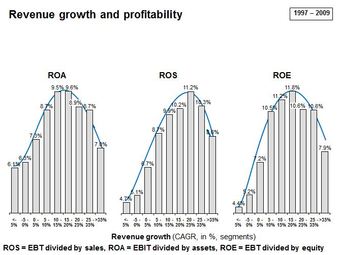

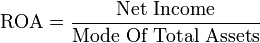

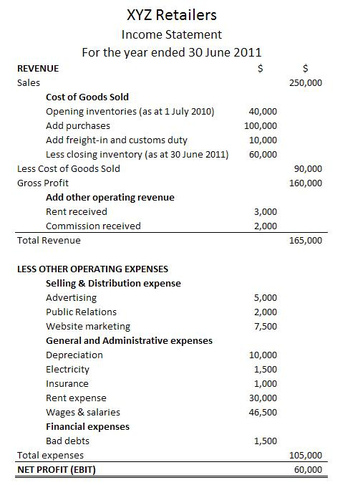

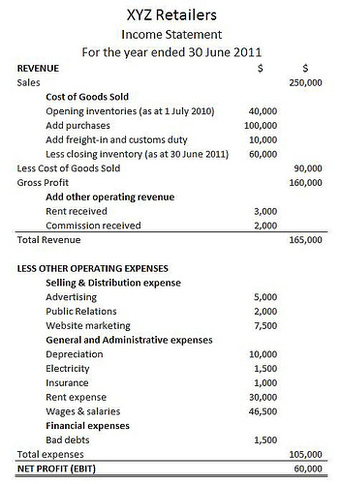

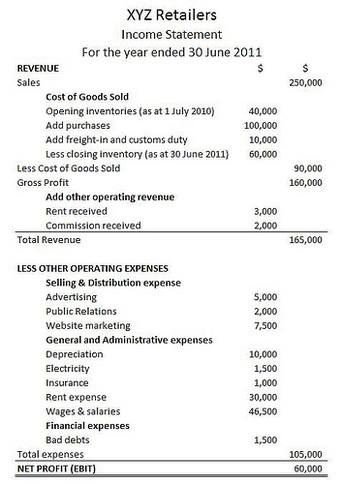

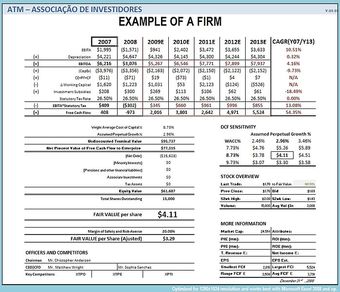

Stock market indices provide invaluable information for investors and accountants. For example, the current market price per share, market capitalization, and trading volume are all readily available. With this information, along with a company’s consolidated financial statements, the following ratios and calculations can be performed:

- Dividend yield on common stock ratio=Dividend per share of common stock

- Payout ratio on common stock = Dividend per share of common stock

- Earnings per share (EPS)

By comparing the above ratios with those of other companies, investors, accountants, and forecasters can determine the position and health of their respective company’s stock.

7.5: Stock Valuation

7.5.1: Expected Dividends, No Growth

A no-growth company would be expected to return high dividends under traditional finance theory.

Learning Objective

Describe how a company should make a dividend decision when it expect no growth

Key Points

- Companies generally either retain earnings for investment, or distribute them as dividend, according to their growth strategy.

- Clientele effects suggests that different dividend levels attract different types of investors.

- Value investors look for indications that a stock is undervalued. High dividends are one indication of undervaluation.

- Knowing a firm’s cost of capital is needed in order to make better decisions. Managers make capital budgeting decisions while capital providers make decisions about lending and investment.

Key Term

- clientele

-

The body or class of people who frequent an establishment or purchase a service, especially when considered as forming a more-or-less homogeneous group of clients in terms of values or habits.

The Dividend Decision

Whether to issue dividends and what amount is calculated mainly on the basis of the company’s unappropriated profit and its earning prospects for the coming year. The amount is also often calculated based on expected free cash flows, which means cash remaining after all business expenses, and capital investment needs have been met.

If there are no favorable investment opportunities–projects where return exceed the hurdle rate–finance theory suggests that management will return excess cash to shareholders as dividends. However, there are exceptions. For example, shareholders of a “growth stock,” expect that the company will, almost by definition, retain earnings so as to fund growth internally.

At the other end of the spectrum, investors of a “no growth,” or value stock will expect the firm to retain little cash for investment, and to distribute a comparatively greater proportion to investors as a dividend.

Clientele Effects

This suggests that a particular pattern of dividend payments may suit one type of stock holder more than another; this is sometimes called the “clientele effect. ” A retiree may prefer to invest in a firm that provides a consistently high dividend yield, whereas a person with a high income from employment may prefer to avoid dividends due to their high marginal tax rate on income. If clienteles exist for particular patterns of dividend payments, a firm may be able to maximize its stock price and minimize its cost of capital by catering to a particular clientele. This model may help to explain the relatively consistent dividend policies followed by mostlisted companies.

Value Investors

No growth, high dividend stocks may appeal to value investors. Value investing involves buying securities with shares that appear underpriced by some form of fundamental analysis. As examples, such securities may be stock in public companies that have high dividend yields, low price-to-earning multiples, or have low price-to-book ratios. Thus, high dividends and low reinvestment of retained earnings can signal an appealing value stock to an investor.

Investing trade-offs

Value investors trade growth for dividends.

7.5.2: Expected Dividends and Constant Growth

Valuations rely heavily on the expected growth rate of a company; past growth rate of sales and income provide insight into future growth.

Learning Objective

Calculate a company’s stock price using the Constant Growth Approximation

Key Points

- Companies are constantly changing, as well as the economy. Solely using historical growth rates to predict the future is not an acceptable form of valuation. Calculating the future growth rate requires personal investment research.

- A generalized version of the Walter model (1956), SPM considers the effects of dividends, earnings growth, as well as the risk profile of a firm on a stock’s value.

- The Gordon model or Gordon’s growth model is the best known of a class of discounted dividend models. It assumes that dividends will increase at a constant growth rate (less than the discount rate) forever.

Key Term

- Gordon Growth Model

-

Gordon Growth Model is also called the dividend discount model (DDM), which is a way of valuing a company based on the theory that a stock is worth the discounted sum of all of its future dividend payments.

Growth Rate

Valuations rely very heavily on the expected growth rate of a company. One must look at the historical growth rate of both sales and income to get a feeling for the type of future growth expected. However, companies are constantly changing, as well as the economy, so solely using historical growth rates to predict the future is not an acceptable form of valuation. Instead, they are used as guidelines for what future growth could look like if similar circumstances are encountered by the company. Calculating the future growth rate requires personal investment research. This may take form in listening to the company’s quarterly conference call or reading a press release or other another company article that discusses the company’s growth guidance. However, although companies are in the best position to forecast their own growth, they are far from accurate. Unforeseen events could cause rapid changes in the economy and in the company’s industry.

And for any valuation technique, it’s important to look at a range of forecast values.

- For example, if the company being valued has been growing earnings between 5 and 10% each year for the last five years, but believes that it will grow 15 – 20% this year, a more conservative growth rate of 10 – 15% would be appropriate in valuations.

- Another example would be for a company that has been going through restructuring. They may have been growing earnings at 10 – 15% over the past several quarters / years because of cost cutting, but their sales growth could be only 0 – 5%. This would signal that their earnings growth will probably slow when the cost cutting has fully taken effect. Therefore, forecasting an earnings growth closer to the 0 – 5% rate would be more appropriate rather than the 15 – 20%. Nonetheless, the growth rate method of valuations relies heavily on gut feel to make a forecast. This is why analysts often make inaccurate forecasts. It is also why familiarity with a company is essential before making a forecast.

Sum of Perpetuities Method

The PEG ratio is a special case in the Sum of Perpetuities Method (SPM) equation. A generalized version of the Walter model (1956), SPM considers the effects of dividends, earnings growth, as well as the risk profile of a firm on a stock’s value. Derived from the compound interest formula using the present value of a perpetuity equation, SPM is an alternative to the Gordon Growth Model. The variables are:

- P is the value of the stock or business

- E is a company’s earnings

- G is the company’s constant growth rate

- K is the company’s risk adjusted discount rate

- D is the company’s dividend payment

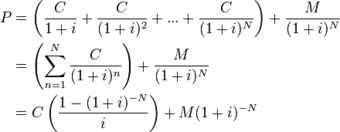

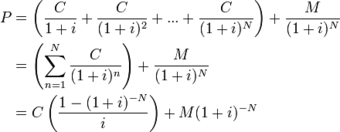

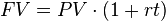

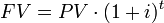

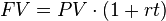

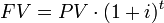

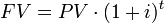

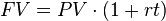

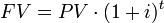

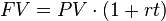

Constant Growth Approximation

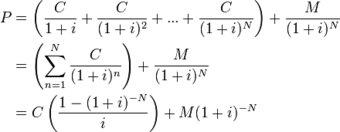

The Gordon model or Gordon’s growth model is the best known of a class of discounted dividend models . It assumes that dividends will increase at a constant growth rate (less than the discount rate) forever. The valuation is given by the formula:

Your Dividend

DDM can be used to calculate a constant growth company.

7.5.3: Relationship Between Dividend Payments and the Growth Rate

The portion of the earnings not paid to investors is, ideally, left for investment in order to provide for future earnings growth.

Learning Objective

Describe the relationship between dividend payments and a company’s growth

Key Points

- Investors take into account how much capital is distributed to investors, and conversely how much capital is kept from investors.

- Investors hope that firms will use retained earnings to either maximize their current operations or invest in such as a way as to lead to higher profits.

- Some firms are unable to distribute earnings, since their funds are tied up in maintenance, repairs, et cetera.

- On the other hand, some companies can retain earnings and put that money back to work – i.e., invest in growth opportunities.

Key Term

- capital gains

-

Profit that results from a disposition of a capital asset, such as stock, bond, or real estate due to arbitrage.

From an investor’s point of view, the fundamentals of a company are of the utmost importance. One such fundamental that that investors take into account is how much capital is distributed to investors, and conversely how much capital is kept from investors. Capital is distributed to investors via dividend payments and, indirectly, through capital gains. Capital that is kept from investors is known as retained earnings. Investors hope that firms will use retained earnings to either maximize their current operations or invest in such as a way as to lead to higher profits. In other words, the portion of profits not paid out to investors via dividends is, ideally, left for investment in order to provide for future earnings growth.

Some companies require large amounts of new capital just to continue operations. Such firms are usually unable to distribute earnings, since their funds are tied up in maintenance, repairs, et cetera. These companies also provide limited growth opportunities, since earnings are not reinvested for the purpose of growth. On the other hand, some companies can retain earnings and put that money back to work – i.e., invest in growth opportunities. Firms that can do this tend to retain more of their earnings. These firms are attractive to investors, even though there is relatively low distribution of profits.

Put succinctly, investors seeking high current income and limited capital growth prefer companies with a high dividend payout ratio. However, investors seeking higher capital growth may prefer a lower payout ratio because capital gains are taxed at a lower rate. High growth firms in early life generally have low or zero payout ratios in order to reinvest as much of their earnings as possible. As they mature, they tend to return more of the earnings back to investors. Note that dividend payout ratio is calculated as dividend per share divided by earnings per share.

7.5.4: Understanding Future Stock Value

There are many different ways to appraise the future value of stocks, including fundamental criteria and stock valuation methods.

Learning Objective

Describe different ways of valuing stock

Key Points

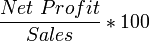

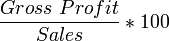

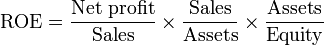

- Earnings Per Share is the total net income of the company divided by the number of shares outstanding; the Profits/Earnings ratio is the stock price divided by the annual EPS figure.

- Return on Invested Capital measures how much money the company makes each year per dollar of invested capital and approximates the expected level of growth; Return on Assets measures the company’s ability to make money from its assets.

- To measure Market Capitalization (the value of all of a company’s stock), multiply the current stock price by the fully diluted shares outstanding; Enterprise Value is equal to the total value the company is trading for on the stock market.

- Enterprise Value (EV) to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) is one of the best measurements of whether or not a company should be valued as cheap or expensive.

Key Terms

- GAAP

-

Generally Accepted Accounting Principles refer to the standard framework of guidelines, conventions, and rules accountants are expected to follow in recording, summarizing, and preparing financial statements in any given jurisdiction.

- risk premium

-

A risk premium is the minimum amount of money by which the expected return on a risky asset must exceed the known return on a risk-free asset, or the expected return on a less risky asset, in order to induce an individual to hold the risky asset rather than the risk-free asset.

Example

- P/E Ratio: For example, if the stock is trading at 10 and the EPS is 0.50, the P/E is 20 times. To get a good feeling of what P/E multiple a stock trades at, be sure to look at both the historical and forward ratios.

In financial markets, stock valuation involves calculating theoretical values of companies and their stocks. The main use of stock valuation is to predict future market prices and profit from price changes. Stocks that are judged as undervalued (with respect to their theoretical value) are bought, while stocks that are perceived to be overvalued are sold, in the expectation that undervalued stocks will, on the whole, rise, while overvalued stocks will, on the whole, fall .

Stock Valuation

Stock valuation involves many methods.

Fundamental Criteria (Fair Value)

The soundest stock valuation method, the discounted cash flow (DCF) method of income valuation, involves discounting the profits (dividends, earnings, or cash flows) the stock will bring to stockholders in the foreseeable future, and calculating a final value on disposal. The discounted rate normally includes a risk premium which is often based on the capital asset pricing model.

Stock Valuation Methods

There are many different ways to value stocks. The key is to take each approach into account while formulating an overall opinion of the stock. If the valuation of a company is lower or higher than other similar stocks, then the next step would be to determine the reasons for the discrepancy.

1. Earnings Per Share (EPS)

EPS is the total net income of the company divided by the number of shares outstanding. Numbers are usually reported as a GAAP EPS number (which means it is computed using mutually agreed upon accounting rules) and a Pro Forma EPS figure (income is adjusted to exclude any one time items as well as some non-cash items like amortization of goodwill or stock option expenses).

2. Price to Earnings (P/E)

Once one has several EPS figures (historical and forecasts), the most common valuation technique used by analysts is the price to earnings ratio, or P/E. To compute this figure, the stock price is divided by the annual EPS figure.

3. Price Earnings to Growth (PEG) Ratio

This valuation technique has become more popular over the past decade or so. It is better than just looking at a P/E because it takes three factors into account: the price, earnings, and earnings growth rates. To compute the PEG ratio, divide the Forward P/E by the expected earnings growth rate (historical P/E and historical growth rate are also used to see where the stock has traded in the past).

4. Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

This valuation technique measures how much money the company makes each year per dollar of invested capital. Invested capital is the amount of money invested in the company by both stockholders and debtors. The ratio is expressed as a percent and Return on Invested Capital ratio should have a percent that approximates the expected level of growth. In its simplest definition, this ratio measures the investment return that management is able to get for its capital. The higher the number, the better the return.

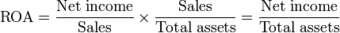

5. Return on Assets (ROA)

Similar to ROIC, ROA, expressed as a percent, measures the company’s ability to make money from its assets. To measure the ROA, take the pro forma net income divided by the total assets. However, because of very common irregularities in balance sheets (due to things like goodwill, write-offs, discontinuations, etc. ) this ratio is not always a good indicator of the company’s potential. If the ratio is higher or lower than expected, be sure to look closely at the assets to see what could be overstating or understating the figure.

6. Price to Sales (P/S)

This figure is useful because it compares the current stock price to the annual sales. In other words, it tells you how much the stock costs per dollar of sales earned.

7. Market Cap

Market Cap, which is short for Market Capitalization, is the value of all of the company’s stock. To measure it, multiply the current stock price by the fully diluted shares outstanding.

8. Enterprise Value (EV)

Enterprise Value is equal to the total value of the company, as trading on the stock market. To compute it, add the Market Cap (see above) and the total net debt of the company.

9. EBITDA

EBITDA stands for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. It is one of the best measures of a company’s cash flow and is used for valuing both public and private companies.

10. EV to EBITDA

This is perhaps one of the best measurements of whether or not a company should be valued as cheap or expensive. To compute, divide the EV by EBITDA (see above for calculations). The higher the number, the more expensive the company is.

7.5.5: Valuing Nonconstant Growth Dividends

Limited high-growth approximation, implied growth models, and the imputed growth acceleration ratio are used to value nonconstant growth dividends.

Learning Objective

Describe the limitations of valuing a company with dividends that have a nonconstant growth rate

Key Points

- Limited high-growth approximation: When a stock has a significantly higher growth rate than its peers, it is sometimes assumed that the earnings growth rate will be sustained for a short time (say, 5 years), and then the growth rate will revert to the mean.

- Implied Growth Models: One can use the Gordon model or the limited high-growth period approximation model to impute an implied growth estimate.

- Imputed growth acceleration ratio: Subsequently, one can divide this imputed growth estimate by recent historical growth rates.

Key Terms

- DCF models

-

Valuation using discounted cash flows is a method for determining the current value of a company using future cash flows adjusted for time value. The future cash flow set is made up of the cash flows within the determined forecast period and a continuing value that represents the cash flow stream after the forecast period.

- break-even

-

Break-even (or break even) is the point of balance between making either a profit or a loss.

Limited high-growth period approximation

When a stock has a significantly higher growth rate than its peers, it is sometimes assumed that the earnings growth rate will be sustained for a short time (say, 5 years), and then the growth rate will revert to the mean. This is probably the most rigorous approximation that is practical.

While these DCF models are commonly used, the uncertainty in these values is hardly ever discussed. Note that the models diverge for and hence are extremely sensitive to the difference of dividend growth to discount factor. One might argue that an analyst can justify any value (and that would usually be one close to the current price supporting his call) by fine-tuning the growth/discount assumptions.

Implied Growth Models

One can use the Gordon model or the limited high-growth period approximation model to impute an implied growth estimate. To do this, one takes the average P/E and average growth for a comparison index, uses the current (or forward) P/E of the stock in question, and calculates what growth rate would be needed for the two valuation equations to be equal. This gives you an estimate of the “break-even” growth rate for the stock’s current P/E ratio. (Note: we are using earnings not dividends here because dividend policies vary and may be influenced by many factors including tax treatment).

Imputed growth acceleration ratio

Subsequently, one can divide this imputed growth estimate by recent historical growth rates. If the resulting ratio is greater than one, it implies that the stock would need to experience accelerated growth relative to its prior recent historical growth to justify its current P/E (higher values suggest potential overvaluation). If the resulting ratio is less than one, it implies that either the market expects growth to slow for this stock or that the stock could sustain its current P/E with lower than historical growth (lower values suggest potential undervaluation). Comparison of the IGAR across stocks in the same industry may give estimates of relative value. IGAR averages across an industry may give estimates of relative expected changes in industry growth (e.g. the market’s imputed expectation that an industry is about to “take-off” or stagnate). Naturally, any differences in IGAR between stocks in the same industry may be due to differences in fundamentals, and would require further specific analysis.

7.6: Valuing the Corporation

7.6.1: Valuing the Corporation

Three approaches are commonly used in corporation valuation: the income approach, the asset-based approach, and the market approach.

Learning Objective

Distinguish between the income, asset-based, and market approaches for corporate valuation

Key Points

- Income approaches include Discount or capitalization rates, Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), Modified Capital Asset Pricing Model, and Weighted average cost of capital (“WACC”).

- The asset approach to business valuation is based on the principle of substitution: no rational investor will pay more for the business assets than the cost of procuring assets of similar economic utility.

- The market approach to business valuation is rooted in the economic principle of competition: in a free market the supply and demand forces will drive the price of business assets to a certain equilibrium.

Key Terms

- net asset value

-

Net asset value (NAV) is the value of an entity’s assets less the value of its liabilities, often in relation to open-end or mutual funds, since shares of such funds registered with the U.S.

- corporation

-

a group of individuals, created by law or under authority of law, having a continuous existence independent of the existences of its members, and powers and liabilities distinct from those of its members

- discounted cash flow

-

In finance, discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis is a method of valuing a project, company, or asset using the concepts of the time value of money. All future cash flows are estimated and discounted to give their present values (PVs)–the sum of all future cash flows, both incoming and outgoing, is the net present value (NPV), which is taken as the value or price of the cash flows in question.

Corporation valuation is a process and a set of procedures used to estimate the economic value of an owner’s interest in a business. Valuation is used by financial market participants to determine the price they are willing to pay or receive to perfect the sale of a business. In addition to estimating the selling price of a business, the same valuation tools are often used by business appraisers to resolve disputes related to estate and gift taxation, divorce litigation, allocate business purchase price among business assets, establish a formula for estimating the value of partners’ ownership interest for buy-sell agreements, and many other business and legal purposes.

Three different approaches are commonly used in business valuation: the income approach, the asset-based approach, and the market approach. Within each of these approaches, there are various techniques for determining the value of a business using the definition of value appropriate for the appraisal assignment. Generally, the income approach determines value by calculating the net present value of the benefit stream generated by the business (discounted cash flow); the asset-based approach determines value by adding the sum of the parts of the business (net asset value); and the market approach determines value by comparing the subject company to other companies in the same industry, of the same size, and/or within the same region.

1. Income approaches

- Discount or Capitalization Rates

A discount rate or capitalization rate is used to determine the present value of the expected returns of a business. The discount rate and capitalization rate are closely related to each other, but are distinguishable. Generally speaking, the discount rate or capitalization rate may be defined as the yield necessary to attract investors to a particular investment, given the risks associated with that investment.

- Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)

The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) is one method of determining the appropriate discount rate in business valuations. The CAPM method originated from the Nobel Prize winning studies of Harry Markowitz, James Tobin, and William Sharpe. The CAPM method derives the discount rate by adding a risk premium to the risk-free rate. In this instance, however, the risk premium is derived by multiplying the equity risk premium times “beta,” which is a measure of stock price volatility. Beta is published by various sources for particular industries and companies. Beta is associated with the systematic risks of an investment.

- Modified Capital Asset Pricing Model

The Cost of Equity (Ke) is computed by using the Modified Capital Asset Pricing Model

CAPM Model ke = Rf + B ( Rm-Rf) + SCRP + CSRP Where: Rf = Risk free rate of return (Generally taken as 10-year Government Bond Yield) B = Beta Value (Sensitivity of the stock returns to market returns) Ke = Cost of Equity Rm= Market Rate of Return SCRP = Small Company Risk Premium, CSRP= Company specific Risk premium

- Weighted Average Cost of Capital (“WACC”)

The weighted average cost of capital is an approach used to determine a discount rate. The WACC method determines the subject company’s actual cost of capital by calculating the weighted average of the company’s cost of debt and cost of equity. The WACC must be applied to the subject company’s net cash flow to total invested capital.

2. Asset-Based Approaches

The value of asset-based analysis of a business is equal to the sum of its parts. That is the theory underlying the asset-based approaches to business valuation. The asset approach to business valuation is based on the principle of substitution: no rational investor will pay more for the business assets than the cost of procuring assets of similar economic utility. In contrast to the income-based approaches, which require the valuation professional to make subjective judgments about capitalization or discount rates, the adjusted net book value method is relatively objective.

3. Market Approaches

The market approach to business valuation is rooted in the economic principle of competition: that in a free market the supply and demand forces will drive the price of business assets to a certain equilibrium. Buyers would not pay more for the business, and the sellers will not accept less than the price of a comparable business enterprise. It is similar in many respects to the “comparable sales” method that is commonly used in real estate appraisal. The market price of the stocks of publicly traded companies engaged in the same or a similar line of business, whose shares are actively traded in a free and open market, can be a valid indicator of value when the transactions in which stocks are traded are sufficiently similar to permit meaningful comparison.

7.6.2: Discounted Dividend vs. Corporate Valuation

The dividend discount model values a firm at the discounted sum of all of its future dividends, and does not factor in income or assets.

Learning Objective

Calculate a company’s stock price using the discounted dividend formula

Key Points

- P = D1 / ( r – g ). P is the current stock price, g is the constant growth rate in perpetuity expected for the dividends, r is the constant cost of equity for that company, and D1 is the value of the next year’s dividends.

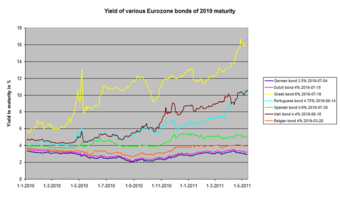

- The equation can also be understood to generate the value of a stock such that the sum of its dividend yield (income) plus its growth (capital gains) equals the investor’s required total return.