11.1: Overview of Bonds

11.1.1: Characteristics of Bonds

In finance, bonds are a form of debt: the creditor is the bond holder, the debtor is the bond issuer, and the interest is the coupon.

Learning Objective

Summarize the characteristics of a bond

Key Points

- Interest on bonds, or coupon payments, are normally payable in fixed intervals, such as semiannually, annually, or monthly.

- Variations exist in bond types, payment terms, and features.

- The yield is the rate of return received from investing in the bond.

- The issuer has to repay the nominal amount on the maturity date.

Key Terms

- par

-

Equal value; equality of nominal and actual value; the value expressed on the face or in the words of a certificate of value, as a bond or other commercial paper.

- perpetuity

-

An annuity in which the periodic payments begin on a fixed date and continue indefinitely.

- coupon

-

Any interest payment made or due on a bond, debenture, or similar.

Overview Of Bonds

Bonds are debt instruments issued by bond issuers to bond holders. A bond is a debt security under which the bond issuer owes the bond holder a debt including interest or coupon payments and or a future repayment of the principal on the maturity date. Variations exist in bond types, payment terms, and features.

Interest on bonds, or coupon payments, are normally payable in fixed intervals, such as semiannually, annually, or monthly. Ownership of bonds are often negotiable and transferable to secondary markets. Bonds provide the borrower with external funds to finance long-term investments, or, in the case of government bonds, to finance current expenditure .

Government Bond

This is an image of a state-issued debt instrument including all the essential information for the indenture.

Bonds and stocks are both securities, but the major difference between the two is that stockholders have an equity stake in the company, whereas bondholders have a creditor stake in the company. Another difference is that bonds usually have a defined term, or maturity, after which the bond is redeemed, whereas stocks may be outstanding indefinitely. An exception is an irredeemable bond, such as a perpetuity.

Principal

Nominal, principal, par, or face amount—the amount on which the issuer pays interest, and which, most commonly, has to be repaid at the end of the term.

Maturity

The issuer has to repay the nominal amount on the maturity date. As long as all due payments have been made, the issuer has no further obligations to the bond holders after the maturity date. The length of time until the maturity date is often referred to as the term or maturity of a bond. In the market for United States Treasury securities, there are three categories of bond maturities:

- short term (bills): maturities between one to five year (instruments with maturities less than one year are called money market instruments)

- medium term (notes): maturities between six to twelve years

- long term (bonds): maturities greater than twelve years

Coupon

The coupon is the interest rate that the issuer pays to the bond holders. Usually this rate is fixed throughout the life of the bond. It can also vary with a money market index, such as LIBOR, or it can be even more exotic.

Yield

The yield is the rate of return received from investing in the bond. It usually refers either to the current yield, or running yield, which is simply the annual interest payment divided by the current market price of the bond. It can also refer to the yield to maturity or redemption yield, which is a more useful measure of the return of the bond, taking into account the current market price, and the amount and timing of all remaining coupon payments and of the repayment due on maturity. It is equivalent to the internal rate of return of a bond.

Credit Quality

The “quality” of the issue refers to the probability that the bondholders will receive the amounts promised on the due dates. This will depend on a wide range of factors. High-yield bonds are bonds that are rated below investment grade by the credit rating agencies. As these bonds are more risky than investment-grade bonds, investors expect to earn a higher yield. Therefore, because of the inherent riskiness of these bonds, they are also called high-yield or “junk” bonds.

Market Price

The market price of a tradeable bond will be influenced among other things by the amounts, currency, the timing of the interest payments and capital repayment due, the quality of the bond, and the available redemption yield of other comparable bonds which can be traded in the markets.

The issue price at which investors buy the bonds when they are first issued will typically be approximately equal to the nominal amount. The net proceeds that the issuer receives are thus the issue price less issuance fees.

Optionality

Occasionally a bond may contain an embedded option:

Callability — Some bonds give the issuer the right to repay the bond before the maturity date on the call dates. Most callable bonds allow the issuer to repay the bond at par. With some bonds, the issuer has to pay a premium. This is mainly the case for high-yield bonds. These have very strict covenants, restricting the issuer in its operations. To be free from these covenants, the issuer can repay the bonds early, but only at a high cost.

Putability — Some bonds give the holder the right to force the issuer to repay the bond before the maturity date on the put dates. These are referred to as retractable or putable bonds.

11.1.2: Types of Bonds

In finance, there are many different types of bonds that vary in term agreements, duration, structure, source, and other characteristics.

Learning Objective

Differentiate be the various types of bonds including secured and unsecured, registered and unregistered and convertible

Key Points

- Bonds can be either secured or unsecured.

- Bonds can be registered or unregistered.

- Some bonds are exchangeable or convertible.

Key Terms

- principal

-

The money originally invested or loaned, on which basis interest and returns are calculated.

- default

-

The condition of failing to meet an obligation.

- coupon

-

Any interest payment made or due on a bond, debenture or similar (no longer by a physical coupon).

- secured bond

-

a debt security in which the borrower pledges some asset as collateral

- debenture

-

A certificate that certifies an amount of money owed to someone; a certificate of indebtedness.

- convertible bond

-

a type of debt security that the holder can convert into shares of common stock in the issuing company or cash of equal value, at an agreed-upon price

In finance, there are many types of bonds. This section provides a overview of the most common types that exist in the financial world today.

Secured bonds

This is a bond for which a company has pledged specific property to ensure its payment.

Mortgage bonds

The most common secured bonds. It is a legal claim (lien) on specific property that gives the bondholder the right to possess the pledged property if the company fails to make required payments.

Unsecured bonds

A debenture bond, or simply a debenture. This is an unsecured bond backed only by the general creditworthiness of the issuer, not by a lien on any specific property. More easily issued by a company that is financially sound.

Registered bonds

This bears the owner’s name on the bond certificate and in the register of bond owners kept by the bond issuer or its agent, the registrar. Bonds may be registered as to principal (or face value of the bond) or as to both principal and interest. Most bonds in our economy are registered as to principal only. For a bond registered as to both principal and interest, the issuer pays the bond interest by check. To transfer ownership of registered bonds, the owner endorses the bond and registers it in the new owner’s name.Therefore, owners can easily replace lost or stolen registered bonds.

Unregistered (bearer) bonds

This is the property of its holder or bearer and the owner’s name does not appear on the bond certificate or in a separate record. Physical delivery of the bond transfers ownership.

Coupon bonds

These are not registered as to interest. Coupon bonds carry detachable coupons for the interest they pay. At the end of each interest period, the owner clips the coupon for the period and presents it to a stated party, usually a bank, for collection.

Term bonds and serial bonds

A term bond matures on the same date as all other bonds in a given bond issue. Serial bonds in a given bond issue have maturities spread over several dates. For instance, one-fourth of the bonds may mature on 2011 December 31, another one-fourth on 2012 December 31, and so on.

Callable bonds

These contain a provision that gives the issuer the right to call (buy back) the bond before its maturity date, similar to the call provision of some preferred stocks. A company is likely to exercise this call right when its outstanding bonds bear interest at a much higher rate than the company would have to pay if it issued new but similar bonds. The exercise of the call provision normally requires the company to pay the bondholder a call premium of about USD 30 to USD 70 per USD 1,000 bond. A call premium is the price paid in excess of face value that the issuer of bonds must pay to redeem (call) bonds before their maturity date.

Convertible bonds

A convertible bond may be exchanged for shares of stock of the issuing corporation at the bondholder’s option. These bonds have a stipulated conversion rate of some number of shares for each USD 1,000 bond. Although any type of bond may be convertible, issuers add this feature to make risky debenture bonds more attractive to investors.

Bonds with stock warrants

A stock warrant allows the bondholder to purchase shares of common stock at a fixed price for a stated period. Warrants issued with long-term debt may be nondetachable or detachable. A bond with nondetachable warrants is virtually the same as a convertible bond; the holder must surrender the bond to acquire the common stock. Detachable warrants allow bondholders to keep their bonds and still purchase shares of stock through exercise of the warrants.

Junk bonds (High-yield bonds)

These are high-interest rate, high-risk bonds. Many junk bonds issued in the 1980s financed corporate restructurings. These restructurings took the form of management buyouts (called leveraged buyouts or LBOs), and hostile or friendly takeovers of companies by outside parties. By early 1990s, junk bonds lost favor as many issuers defaulted on their interest payments. Some issuers declared bankruptcy or sought relief from the bondholders by negotiating new debt terms.

Fixed rate bonds

These have a coupon that remains constant throughout the life of the bond. A variation is stepped-coupon bonds, whose coupon increases during the life of the bond.

Floating rate notes

Also known as FRNs or floaters, these have a variable coupon that is linked to a reference rate of interest, such as LIBOR or Euribor.

Zero-coupon bonds

Zeros pay no regular interest. They are issued at a substantial discount to par value, so that the interest is effectively rolled up to maturity (and usually taxed as such). The bondholder receives the full principal amount on the redemption date.

Exchangeable bonds

These allow for exchange to shares of a corporation other than the issuer.

War bond

These are issued by a country to fund a war.

Municipal bond

These are bonds issued by a state, U.S. Territory, city, local government, or their agencies. Interest income received by holders of municipal bonds is often exempt from the federal tax and the issuing state’s income tax. Some municipal bonds issued for certain purposes may not be tax exempt.

Treasury bond

Also called a government bond, this is issued by the Federal government and is not exposed to default risk. It is characterized as the safest bond, with the lowest interest rate. Backed by the “full faith and credit” of the federal government, this type of bond is often referred to as risk-free.

11.1.3: Issuing Bonds

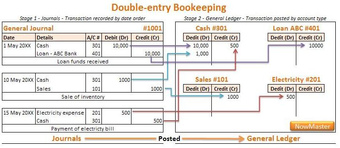

On issuance, the journal entry to record the bond is a debit to cash and a credit to bonds payable.

Learning Objective

Explain how a company would record a bond issue and how to determine the selling price of a bond

Key Points

- Bonds differ from notes payable because a note payable represents an amount payable to only one lender, while multiple bonds are issued to different lenders at the same time.

- Bonds are a form of financing for a company, in which the company agrees to pay the bondholders interest over the life of the bond. When bonds are issued they are classified as long-term liabilities.

- Other journal entries associated with bonds is the accounting for interest each period that interest is payable. The journal entry to record that is a debit interest expense and a credit to cash.

- The amount of risk associated with the company issuing the bond determines the price of the bond. The more risk assessed to a company the higher the interest rate the issuer must pay to bondholders.

Key Terms

- liabilities

-

An amount of money in a company that is owed to someone and has to be paid in the future, such as tax, debt, interest, and mortgage payments.

- journal entry

-

A journal entry, in accounting, is a logging of transactions into accounting journal items. The journal entry can consist of several items, each of which is either a debit or a credit. The total of the debits must equal the total of the credits or the journal entry is said to be “unbalanced. ” Journal entries can record unique items or recurring items, such as depreciation or bond amortization.

Issuing Bonds

Bonds are essentially a form of financing for a company, but instead of borrowing form a bank the company is borrowing from investors. In exchange, the company agrees to pay the bondholders interest at predetermined intervals, for a set amount of time.

Bonds differ from notes payable because a note payable represents an amount payable to only one lender, while multiple bonds are issued to different lenders at the same time. Also, the bondholders may sell their bonds to other investors any time prior to the bonds maturity.

Bond prices

The market price of a bond is expressed as a percentage of nominal value. For example, a bond issued at par is selling for 100% of its face value. Bonds can sell for less than their face value, for example a bond price of 75 means that the bond is selling for 75% of its par (face value).

The amount of risk associated with the company issuing the bond determines the price of the bond. The more risk assessed to a company the higher the interest rate the issuer must pay to buyers. If a bond has a coupon interest rate that is higher than the market interest rate it is considered a premium.

The premium (higher interest rate) is to offset the assumed higher than average risk associated with investing in the company.

Bonds are considered issued at a discount when the coupon interest rate is below the market interest rate.That means a company selling bonds at a discount rate receive less than the face value of the bond in the sale.

When bonds are issued, they are classified as long-term liabilities. On issuance, the journal entry to record the bond is a debit to cash and a credit to bonds payable.

Other journal entries associated with bonds is the accounting for interest each period that interest is payable. The journal entry to record that is a debit interest expense and a credit to cash.

11.1.4: Bonds Payable and Interest Expense

Journal entries are required to record initial value and subsequent interest expense as the issuer pays coupon payments to the bondholder.

Learning Objective

Summarize how a company would record the original issue of the bond and the subsequent interest payments

Key Points

- Issuers must account for interest expense during the term of issued bonds.

- Bonds are recorded at face value, when issued, as a debit to the cash account and a credit to the bonds payable account.

- Bonds require additional entries to record interest expense as the issuer pays coupon payments to the bondholder according to the agreed terms of the bond.

- National governments, municipalities and companies issue bonds to raise cash.

Key Terms

- yield

-

The current return as a percentage of the price of a stock or bond.

- face value

-

The amount or value listed on a bill, note, stamp, etc.; the stated value or amount.

- record date

-

the date at which a shareholder must be registered in order to receive a declared dividend

- coupon

-

Any interest payment made or due on a bond, debenture or similar (no longer by a physical coupon).

Bonds derive their value primarily from two promises made by the borrower to the lender or bondholder. The borrower promises to pay (1) the face value or principal amount of the bond on a specific maturity date in the future, and (2) periodic interest at a specified rate on face value at stated dates, usually semiannually, until the maturity date .

Old Lousianna State Bond

Louisiana “baby bond”, 1874 series, payable 1886

Example of bonds issued at face value on an interest date:-

Valley Company’s accounting year ends on December 31. On 2010 December 31, Valley issued 10-year, 12% yield bonds with a USD 100,000 face value, for USD 100,000. The bonds are dated 2010 December 31, call for semiannual interest payments on June 30 and December 31, and mature on 2020 December 31. Valley made the required interest and principal payments when due. The entries for the 10 years are as follows:

On 2010 December 31, the date of issuance, the entry is:

2010 Dec. 31 Cash (+A) 100,000

Bonds payable (+L) 100,000

To record bonds issued at face value.

On each June 30 and December 31 for 10 years, beginning 2010 June 30 (ending 2020 June 30), the entry would be: Each year June 30 And Dec.31

Bond Interest Expense ($100,000 x 0.12 x½) (-SE) 6,000

Cash (-A) 6,000

To record periodic interest payment. On 2020 December 31, the maturity date, the entry would be:

2020 Dec. 31

Bond interest expense (-SE) 6,000

Bonds payable (-L) 100,000

Cash (-A) 106,000

To record final interest and bond redemption payment.

Note that Valley does not need adjusting entries because the interest payment date falls on the last day of the accounting period. The income statement for each of the 10 years (2010-2018) would show Bond Interest Expense of USD 12,000 (USD 6,000 X 2); the balance sheet at the end of each of the years (2010-2018) would report bonds payable of USD 100,000 in long-term liabilities. At the end of 2019, Valley would reclassify the bonds as a current liability because they will be paid within the next year.

The real world is more complicated. For example, assume the Valley bonds were dated 2010 October 31, issued on that same date, and pay interest each April 30 and October 31. Valley must make an adjusting entry on December 31 to accrue interest for November and December. That entry would be:

2010 Dec. 31

Bond interest expense ($100,000 x 0.12 x 2/12) (-SE) 2,000

Bond interest payable (+L) 2,000

To accrue two month’s interest expense.

The 2011 April 30, entry would be: 2011 Apr. 30

Bond interest expense ($100,000 x 0.12 x(4/12)) (-SE) 4,000

Bond interest payable (-L) 2,000

Cash (-A) 6,000

To record semiannual interest payment.

The 2011 October 31, entry would be:

2011 Oct. 31

Bond interest expense (-SE) 6,000

Cash (-A) 6,000

To record semiannual interest payment.

Each year Valley would make similar entries for the semiannual payments and the year-end accrued interest. The firm would report the USD 2,000 Bond Interest Payable as a current liability on the December 31 balance sheet for each year.

11.2: Valuing Bonds

11.2.1: Factors Affecting the Price of a Bond

A bond’s book value is affected by its term, face value, coupon rate, and discount rate.

Learning Objective

Explain how a bond’s value is affected by its term, face value, coupon and discount rate

Key Points

- A bond’s term, or maturity, is how long the issuing company has until it must repay the entirety of what it owes.

- Otherwise known as the principal or nominal amount, this is the amount of money that the organization issuing the bond has to pay interest on and generally has to repay when the bond is redeemed at the end of the term.

- A bond’s coupon is the interest rate that the business must pay on the bond’s face value.

- The discount rate is a a measure of what the bondholder’s return would be if he invested his money in something other than the bond. In practical terms, the discount rate generally equals the coupon rate or interest rate associated with similar investment securities.

Key Terms

- bond

-

Evidence of a long-term debt, by which the bond issuer (the borrower) is obliged to pay interest when due, and repay the principal at maturity, as specified on the face of the bond certificate. The rights of the holder are specified in the bond indenture, which contains the legal terms and conditions under which the bond was issued. Bonds are available in two forms: registered bonds and bearer bonds.

- discount rate

-

The interest rate used to discount future cashflows of a financial instrument; the annual interest rate used to decrease the amounts of future cashflows to yield their present value.

A bond is a financial security that is created when a person transfers funds to a company or government, with the understanding that at some point in the future the entity issuing the bond will have to repay the amount, plus interest . Generally, the person who holds the actual bond document is the one with the right to receive payment. This allows people who originally acquire a bond to sell it on the open market for an immediate payout, as opposed to waiting for the issuing entity to pay the debt back. Note that the trading value of a bond (its market price) can vary from its face value depending on differences between the coupon and market interest rates.

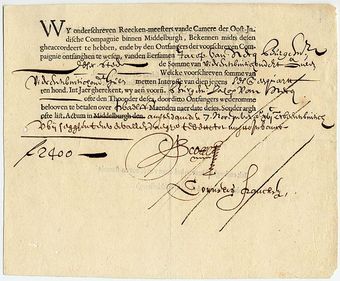

A bond from the Dutch East India Company

A bond is a financial security that represents a promise by a company or government to repay a certain amount, with interest, to the bondholder.

A bond’s book value is determined by several factors.

Term

A bond’s term, or maturity, is how long the issuing company has until it must repay the entirety of what it owes. Sometimes a business will make interest payments during the term of the bond, but a term ends when all of the payments associated with the bond are completed.

Face Value of Bond

Otherwise known as the principal or nominal amount, this is the amount of money that the organization issuing the bond has to pay interest on and generally has to repay when the bond is redeemed at the end of the term. The redemption amount generally equals how much the original investor paid to acquire the bond. However, the redemption amount can be different than the acquisition cost.

Coupon

A bond’s coupon is the interest rate that the business must pay on the bond’s face value. These interest payments are generally paid periodically during the bond’s term, although some bonds pay all the interest it owes at the end of the period. While the coupon rate is generally a fixed amount, it can also be “indexed. ” This means that the interest rate is calculated by taking an established rate that fluctuates over time, such as a bank’s lending rate, and adding a “premium” percentage amount to determine the bond’s coupon rate. As a result, the interest that is paid to the bond holder fluctuates over time with an indexed coupon rate.

Discount Rate

A bond’s value is measured based on the present value of the future interest payments the bond holder will receive. To calculate the present value, each payment is adjusted using the discount rate. The discount rate is a measure of what the bondholder’s return would be if he invested his money in another security. In practical terms, the discount rate generally equals the coupon rate or interest rate associated with similar investment securities.

11.2.2: Bond Valuation Method

A bond’s value is measured by its sale price, but a business can estimate a bond’s price before issuance by calculating its present value.

Learning Objective

Summarize how a company would calculate the value of their bonds

Key Points

- When calculating the present value of a bond, use the market rate as the discount rate.

- Regardless of whether the bond is sold at a premium or discount, a company must list a “bond payable” liability equal to the face value of the bond.

- If the market rate is greater than the bond’s contract rate, the bond will be sold at a discount. If the market rate is less than the bond’s contract rate, the bond will be sold at a premium.

Key Terms

- market interest rate

-

the interest rate determined through various investment systems, such as the stock market or the bond market

- contract rate

-

Another term for coupon rate, this is the amount of interest the business will pay on the principal of the bond.

- market rate

-

The interest rate associated with other bonds that have a similar risk factor.

Bond Valuation

A business must record a liability in its records when it issues a series of bonds. The value of the liability the business will record must equal the amount of money or goods it receives when it issues the bond. Whether the amount the business will receive equals its face value depends on the difference between the bond’s contract rate and the market rate of interest at the time the bond is issued .

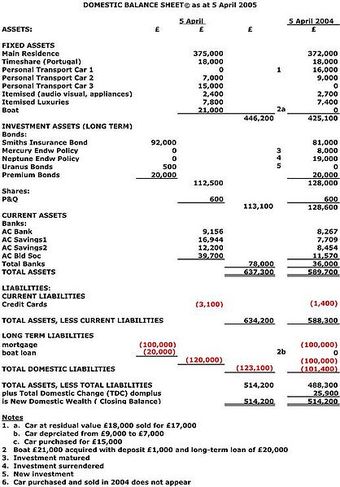

Balance Sheet

A bond issued by a company is recorded as a liability on its balance sheet.

The bond’s contract rate is another term for the bond’s coupon rate. It is what the issuing company uses to calculate what it must pay in interest on the bond. The market rate is what other bonds that have a similar risk pay in interest.

Regardless of what the contract and market rates are, the business must always report a bond payable liability equal to the face value of the bonds issued. If the market rate is greater than the coupon rate, the bonds will probably be sold for an amount less than the bonds’ face value and the business will have to report a “bond discount. ” The value of the bond discount will be the difference between what the bonds’ face value and what the business received when it sold the bonds. If the market rate is less than the coupon rate, the bonds will probably be sold for an amount greater than the bonds’ value. The business will then need to record a “bond premium” for the difference between the amount of cash the business received and the bonds’ face value.

Calculating the Premium and Discount

If the market and coupon rates differ, the issuing company must calculate the present value of the bond to determine what price to charge when it sells the security on the open market. The present value of a bond is composed of two components; the principal and the interest payments. The discount rate for both the principal and interest payment components is the market rate when the bond was issued.

11.2.3: Bonds Issued at Par Value

To record a bond issued at par value, credit the “bond payable” liability account for the total face value of the bonds and debit cash for the same amount.

Learning Objective

Explain how a company would record a bond issued a par value

Key Points

- Recording a bond issued at par value is a simple process, since there is generally no premium or discount associated with the bond’s sale.

- To record interest paid on a bond issued at par value, debit the amount paid to the bond interest expense account and credit the same amount to the cash account.

- When the bond is paid off, record any final interest payment. Then debit the bond payable account and credit the cash account for the full face value of the bonds.

Key Terms

- no-par value stock

-

shares issued by a company without a minimum price for which they must be sold

- par value stock

-

shares with a value stated in the corporate charter below which shares of that class cannot be sold upon initial offering

- par value

-

The amount or value listed on a bill, note, stamp, etc.; the stated value or amount.

Example

- Consider a 3-year bond with a face value of $1,000 and an effective interest rate of 7%, sold at face value. Since the bond is sold at face value, the proceeds are $1,000. The journal entry would be: Cash $1,000 Bond Payable $1,000The interest payable for each period will be equal to 1,000 x 7%, or $70. The affected accounts will be interest expense and cash, and the journal entry will be as follows: Interest Expense $70 Cash $70At bond expiration, the creditor must make a journal entry for the last interest payment and the retirement of the bond through principal payment. The journal entry would be: Bond Payable $1,000 Cash $1,000

Bonds issued at par value are relatively simple to calculate and record. When a bond is issued at par value it is sold for the face value amount. This generally means that the bond’s market and contract rates are equal to each other, meaning that there is no bond premium or discount.

The General Ledger

All transactions made by the company in relation to the bond must be recorded in its general ledger. The general ledger contains all entries from both the General Journal and the Special Journals.

When a business issues a bond, it participates in three types of transactions. First, the business issues the bond in exchange for cash. Next, it generally pays interest during the term of the bond. Finally, it pays off the obligation by repaying the face amount and the last interest payment. Each of these transactions must be recorded in the company’s financial records with a series of journal entries.

Issuing the Bond

When the bond is issued, the company must record a liability called “bond payable. ” This is generally a long-term liability. It is created by recording a credit equal to the face value of all the bonds that are issued. To balance this entry, the company must also debit cash equal to the face value of all the bonds issued. Since the bonds are sold at par value, the amount of cash the company receives should equal the total face value of the issued bonds.

Cash – debit face value (increase cash balance)

Bond payable – credit face value (increase bonds payable)

Interest Payments

When the company makes an interest payment, it must credit, or decrease, its cash balance by the amount it paid in interest. To balance the entry, the company must record a debit equal to the amount it paid in its bond interest expense account.

Bond Interest Expense – debit interest payment (increase interest expense line)

Cash – credit interest payment (decrease cash balance)

Paying Off the Bond

When the bond is paid off, the company must record two transactions. First, it must record any final interest payments that are made. Then, it must record the bond principal being paid off. This is done by debiting the bond payable account and crediting the cash account for the full book value of the bond.

Bond Interest Expense – debit interest payment

Cash – credit final interest payment

Bond Payable – debit face value

Cash – credit face value

11.2.4: Bonds Issued at a Discount

When a business sells a bond at a discount, it must record a discount balance in its records and amortize that amount over the bond’s term.

Learning Objective

Explain how to record a bond issued at a discount

Key Points

- When the bond is sold, the company credits the “bonds payable” liability account by the bonds’ face value. The company debits the cash account by the amount of money it receives from the sale. The difference between the face value and sales price is debited as the discount value.

- The amortization rate for the bond’s discount balance is calculated by dividing the discount amount by the number of periods the company has to pay interest.

- To record interest expense, a business credits the bond discount account by the amortization rate and credits cash by the amount of money it pays in interest expense. Interest expense is debited by the sum of the amortization rate and how much it pays in interest to the bond holder.

- When the bond matures, the business must record the repayment of the principal to the bondholder, as well as all final interest payments. At this time, the discount on bond payable and bond payable accounts must be zeroed out, and all cash payments must be recorded.

Key Term

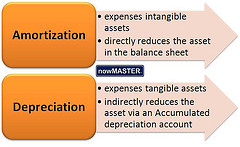

- amortize

-

To wipe out (a debt, liability etc. ) gradually or in installments.

Example

- Assume a business sells a 10 year, $100,000 bond with an effective annual interest rate of 6% for $90,000. The journal entry for that transaction would be as follows: Cash $90,000 Discount $10,000 Bond Payable $100,000The interest expense each period is $6,000, and the amortization rate on the bond payable equals $1,000 ($100,000/10 years). The total expense each period is $7,000. The journal entry will be: Interest Expense $7,000 Discount $1,000 Cash $6,000When the bond matures, the business must record the repayment of the principal to the bondholder, as well as all final interest payments. In this example, the journal entries will be: Interest Expense $7,000 Discount $1,000 Cash $6,000 Bond Payable $100,000 Cash $100,000

Issuing Bonds at a Discount

For the issuer, recording a bond issued at a discount can be a little more difficult than recording a bond issued at par value. Because the issuer receives less cash for the bond than the face value, this difference must be recorded in the company records as a discount expense. When a bond is sold at a discount, the market rate of the bond exceeds the contract rate. As a result, the bond must be sold at an amount less than its face value. In addition, that discounted amount must be amortized over the term of the bond. When the company amortizes the discount associated with the bond, it increases its interest expense beyond what it actually pays to the bondholder.

Amortization & depreciation in the accounting cycle

A bond’s discount amount must be amortized over the term of the bond.

Recording the Bond Sale

When a bond is sold, the company records a liability by crediting the “bonds payable” account for the bond’s total face value. Next, the company debits the cash account by the amount of money it receives from the bond sale. The business then debits the difference between the bond’s face value and what it receives in cash from the sale. That is the discount amount.

Assume a business sells a 10 year, $100,000 bond for $90,000. The journal entry for that transaction would be as follows:

Cash $90,000 Dr.

Discount on Bond Payable $10,000 Dr.

Bond Payable $100,000 Cr.

Recording Interest Payments

As the company pays interest, the discount on the bond payable is amortized. Generally, the amortization rate is calculated by dividing the discount by the number of periods the company has to pay interest.

Using the example from above, assume the company pays 6% interest on the $100,000 bond annually. That means that the amortization rate on the bond payable equal $1,000 ($100,000/10 years). While the business would only have to pay the bondholder $6,000 in cash, its total interest expense equals $7,000, or the amount of interest it pays plus the amortization rate. The journal entry would be:

Bond Interest Expense $7,000 Dr.

Discount on Bond Payable $1,000 Cr.

Cash $6,000 Cr.

Recording Bond Maturity

When the bond matures, the business must record the repayment of the principal to the bondholder, as well as all final interest payments. At this time, the discount on bond payable and bond payable accounts must be zeroed out, and all cash payments must be recorded.

Using our example from above, the final set of bond journal entries should look like this:

Bond Interest Expense $7,000 Dr.

Discount on Cash Payable $1,000 Cr.

Cash $6,000 Cr.

Bond Payable $100,000 Dr.

Cash $100,000 Cr.

11.2.5: Bonds Issued at a Premium

When a bond is sold at a premium, the difference between the sales price and face value of the bond must be amortized over the bond’s term.

Learning Objective

Explain how to record bonds issued at a premium

Key Points

- When the bond is issued, the company must debit the cash by the amount that the business receives, credit a bond payable liability account by an amount equal to the face value of the bonds, and credit a bond premium account by the difference between the sale price and the bond’s face value.

- To calculate the amortization rate of the bond premium, a company generally divides the bond premium amount by the number of interest payments that will be made during the term of the bond.

- When recording interest payments, the company credits cash by the amount paid to the bond holder, debits the bond premium account by the amortization rate, and debit interest expense for the difference between the amount paid in interest and the premium’s amortization for the period.

- When the bond reaches maturity, the company must pay the bondholder the face value of the bond, finish amortizing the premium, and pay any remaining interest obligations. When all the final journal entries are made, the bond premium and bond payable account must equal zero.

Key Term

- amortize

-

To wipe out (a debt, liability etc. ) gradually or in installments.

Example

- Assume a business issues a 10-year bond that has an effective annual interest rate of 6%, with a face value of $100,000. This bond sells for $110,000. The resulting journal entry would be: Cash $110,000 Bond Payable $100,000The $10,000 premium would be divided by 10 annual interest payments. This would make the amortization rate of the bond’s premium equal to $1,000 per year. The company must pay $6,000 in interest annually, so the company’s annual interest expense equals $5,000. The resulting journal entry is: Bond Interest Expense $5,000 Bond Premium $1,000 Cash $6,000When the bond reaches maturity, the company must pay the bondholder the face value of the bond, finish amortizing the premium, and pay any remaining interest obligations. In this example, the final journal entries will be: Bond Interest Expense $5,000 Bond Premium $1,000 Cash $6,000 Bond Payable $100,000 Cash $100,000

When a bond is issued at a premium, that means that the bond is sold for an amount greater than the bond’s face value. This generally means that the bond’s contract rate is greater than the market rate. Like with a bond that is sold at a discount, the difference between the bond’s face value and sales price must be amortized over the term of the bond. However, unlike with a bond sold at a discount, the process of amortizing the premium will decrease the bond’s interest expense recorded on the issuing company’s financial records. The issuing company will still be required to pay the bondholder the interest payments guaranteed by the bond.

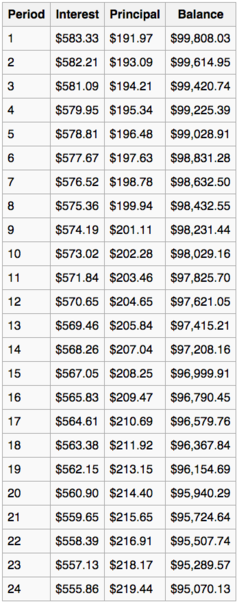

Amortization Schedule

An example of an amortization schedule of a $100,000 loan over the first two years.

Bond Issue

When the bond is issued, the company must debit the cash account by the amount that the business receives for the bond sale. A liability, titled “bond payable,” must be created and credited by an amount equal to the face value of the issued bonds. The difference between the cash from the bond sale and the face value of the bond must be credited to a bond premium account.

For example, assume a business issues a 10-year bond that pays 6% interest annually, with a face value of $100,000. This bond sells for $110,000. The resulting journal entry would be:

Cash – $110,000

Bond Payable – $100,000

Bond Premium – $100,000

Interest Payments on the Bond

When the business pays interest, it must also amortize the bond premium at that time. To calculate the amortization rate of the bond premium, a company generally divides the bond premium amount by the number of interest payments that will be made during the term of the bond. Every time interest is paid, the company must credit cash for the interest amount paid to the bond holder. The company must debit the bond premium account by the amortization rate. The difference between the amount paid in interest and the premium’s amortization for the period is the interest expense for that period.

Using the example from above, the $10,000 premium would be divided by 10 annual interest payments. This would make the amortization rate of the bond’s premium equal to $1,000 per year. The company must pay $6,000 in interest annually, so the company’s annual interest expense equals $5,000. The resulting journal entry is:

Bond Interest Expense – $5,000

Bond Premium – $1,000

Cash – $6,000

Bond Reaches Maturity

When the bond reaches maturity, the company must pay the bondholder the face value of the bond, finish amortizing the premium, and pay any remaining interest obligations. When all the final journal entries are made, the bond premium and bond payable account must equal zero.

Using the example, this is what the final journal entries must look like:

Bond Interest Expense – $5,000

Bond Premium – $1,000

Cash – $6,000

Bond Payable – $100,000

Cash – $100,000

11.2.6: Valuing Zero-Coupon Bonds

The value of a zero-coupon bond equals the present value of its face value discounted by the bond’s contract rate.

Learning Objective

Explain how to value a zero coupon bond

Key Points

- A zero-coupon bond is one that does not make ongoing interest payment to the bondholder over the term of the bond.

- The issuing entity will sell the zero-coupon bond at lower than face value. When the bond’s term is over, the issuing business will repay the bond at its face value.

Key Term

- zero-coupon bond

-

A zero-coupon bond (also called a discount bond or deep discount bond) is a bond bought at a price lower than its face value, with the face value repaid at the time of maturity.

Example

- A zero-coupon bond with requires repayment of $100,000 in 3 years. If the effective interest rate is 7%, what are the proceeds? How much interest expense is recognized? The proceeds will be the present value of $100,000 at 7% for 3 years:

which is equal to $81,629.79. The journal entry for the firm issuing the bond is: Cash 81,629.79 Discount 18,370.21 Bond Payable 100,000.00 The discount is the difference between the bond payable (how much will be repaid at maturity) and the proceeds (the cash initially received); zero-coupon bonds will always be issued at a discount. The discount is a contra-liability linked to the bond payable; this yields a net bond payable of 81,629.79, the bond payable less the discount. Note: this is also the initial proceeds. The effective interest rate method indicates that interest expense must be recognized each period the bond is outstanding, even if no cash interest is being paid. The interest expense is the net payable times the effective rate, in this example:

%Which is 5,714.09. The journal entry to recognized the interest expense is: Interest Expense 5,714.09 Discount 5,714.09 The bond discount is reduced by 5,714.09 to 12,656.12, yielding a net bond payable of 87,343.88. Using the same calculation, the second and third years’ interest expenses of 6,114.07 and 6,542.06 can be calculated. The total interest expense recognized at the end of the third year is 18,370.21, the total of the original discount, which is fully amortized at maturity.

“Beat Back the Hun with Liberty Bonds”

After war was declared, the moral imperative of liberty and the Allied cause was touted in official, government-sponsored propaganda.

A zero-coupon bond is one that does not pay interest over the term of the bond. Instead, the entity will sell the bond at lower than face value. When the bond’s term is over, the issuing business will repay the bond at its face value. The bondholder generates a return paying less than what he receives in payment at the end of the bond’s term.

While the business may not make periodic interest payments, interest income is still generated. The interest income is merely accumulated and paid at the end of the bond’s term.

Formula for Calculating Value of Zero-Coupon Bond

Zero-Coupon Bond Value = Face Value of Bond / (1+ interest Rate)

Generally, the price of a zero-coupon bond is based on the present value of the amount the issuing business will pay the bondholder when the bond matures. The amount the company pays at the end of the term equals the bond’s face value. The present value is determined using the interest rate stated on the bond. The bond’s term is used as the time period in the present value calculation.

It is important when completing the zero-coupon bond calculation to ensure the time period and term of the bond are expressed in similar terms. If the interest rate of the bond is expressed as a monthly rate and the term of the bond is 10 years, the bond term should be expressed as 120 months when making the calculation.

Example Calculation

Assume a business issues a 2 year note, paying 5% interest with a face value of $100,000. To calculate its present value, you would raise 1.05 to the tenth power. This equals 1.1025. You then divide $100,000 by 1.1025. The result is that the bond would have a present value of $90,702.95.

11.3: Bond Retirement

11.3.1: Redeeming at Maturity

The journal entry to record the retirement of a bond: Debit Bonds Payable & Credit Cash.

Learning Objective

Explain how to record the retirement of a bond at maturity

Key Points

- Unless the bond matures in a year or less it is shown on the balance sheet in the long term liabilities section.

- At maturity, all due payments are made, and the issuer has no further obligations to the bond holders after the maturity date.

- On the balance sheet the Bonds Payable account can be shown as different issues or consolidated into a single balance.

- Keep in mind the carrying value – cash paid to retire bonds = gain or loss on bond retirement.

Key Term

- maturity

-

Date when payment is due

Bond Retirement

A maturity date is the date when the bond issuer must pay off the bond. Maturity is generally an indication of when you as an investor will get your money back. Typically, bonds stop earning interest after they mature. As long as all due payments have been made, the issuer has no further obligations to the bondholders after the maturity date.

A bond certificate

A bond certificate issued via the South Carolina Consolidation Act of 1873. How the sale of a bond is recorded on a company’s books depends on how the debt is initially classified by the acquiring investor. Debt securities can be classified as “held-to-maturity,” a “trading security,” or “available-for-sale. “

The carrying value of bonds at maturity will always equal their par value. In other words, par value (nominal, principal, par or face amount), the amount on which the issuer pays interest, and which, most commonly, has to be repaid at the end of the term. For a bond sold at discount, its carrying value will increase and equal their par value at maturity. For a bond sold at premium, its carrying value will decrease and equal the par value at maturity.

Some structured bonds can have a redemption amount that is different from the face amount and can be linked to performance of particular assets such as a stock or commodity index, foreign exchange rate or a fund. This can result in an investor receiving less or more than his original investment at maturity.

Bonds can be classified to coupon bonds and zero coupon bonds. For coupon bonds, the bond issuer is supposed to pay both the par value of the bond and the last coupon payment at maturity. In case of a zero coupon bond, only the amount of par value is paid when the bond is redeemed at maturity.

Bonds Payable & The Balance Sheet

Unless the bond matures in a year or less it is shown on the balance sheet in the long-term liabilities section. If current assets will be used to retire the bonds, a Bonds Payable account should be listed in the current liability section. If the bonds are to be retired and new ones issued, they should remain as a long-term liability. All bond discounts and premiums also appear on the balance sheet.

A separate account should be maintained for each bond issue. On the balance sheet, the Bonds Payable account can be shown as different issues or consolidated into a single balance. If a single balance is shown, then a schedule or note should disclose the details of the bond issues.

A description of bonds issued including the effective interest rate, maturity date, terms, and sinking fund requirements are included in the notes to financial statements.

Redeeming at Maturity

The journal entry to record the retirement of a bond:

Debit Bonds payable

Credit Cash

Keep in mind the carrying value – cash paid to retire bonds = gain or loss on bond retirement

11.3.2: Redeeming Before Maturity

Early redemption happens on issuers or holders’ intentions, more likely as interest rates are falling and bonds contain embedded options.

Learning Objective

Summarize what it means to redeem a bond before maturity

Key Points

- Bonds can be redeemed at or before maturity. Early redemption may happen on bond issuers or bondholders’ intentions.

- Before maturity, the bond is bought back at a premium to compensate for lost interest. It is notable that early repurchase happens more often when the interest rate in the market is on decline and when it is a callable bond.

- Putable bonds give the holder the right to force the issuer to repay the bond before maturity. The price at which bonds are redeemed in this case is predetermined in bond covenants.

Key Terms

- callable bond

-

a type of debt security that allows the issuer of the bond to retain the privilege of redeeming the bond at some point before the bond reaches its date of maturity

- high-yield bonds

-

In finance, a high-yield bond (non-investment-grade bond, speculative-grade bond, or junk bond) is a bond that is rated below investment grade. These bonds have a higher risk of default or other adverse credit events, but typically pay higher yields than better quality bonds in order to make them attractive to investors.

- premium

-

A bonus paid in addition to normal payments.

Bonds can be redeemed at or before maturity. Early redemption may happen on bond issuers or bondholders’ intentions .

Pacific Railroad Bond

$1,000 (30 year, 7%) “Pacific Railroad Bond” (#93 of 200) issued by the City and County of San Francisco.

For bond issuers, they can repurchase a bond at or before maturity. Redemption is made at the face value of the bond unless it occurs before maturity, in which case the bond is bought back at a premium to compensate for lost interest. The issuer has the right to redeem the bond at any time, although the earlier the redemption takes place, the higher the premium usually is. This provides an incentive for companies to do this as rarely as possible. It is notable that early repurchase happens more often when the interest rate in the market is on decline and when the bond contains an embedded option. It grants option-like features to the holder or the issuer. To be detailed, the bond issuer will repurchase bonds with callability.

Some bonds give the issuer the right to repay the bond before the maturity date on the call dates. These bonds are referred to as callable bonds. Most callable bonds allow the issuer to repay the bond at par. With some bonds, the issuer has to pay a premium, the so-called call premium. This is mainly the case for high-yield bonds. These have very strict covenants. They restrict the issuer in its operations. To be free from these covenants, the issuer can repay the bonds early, but only at a high cost.

Bonds with embedded options can also be ones with putability. Some bonds give the holder the right to force the issuer to repay the bond before the maturity date on the put dates. These are referred to as retractable or putable bonds. In this case, the price at which bonds are redeemed is predetermined in bond covenants.

11.4: Reporting and Analyzing Long-Term Liabilities

11.4.1: Reporting Long-Term Liabilities

Debts that become due more than one year into the future are reported as long-term liabilities on the balance sheet.

Learning Objective

Identify a long-term liability

Key Points

- Debts due greater than one year (12 months) into the future are considered long-term.

- If a classified balance sheet is being utilized, the current portion of the long-term liability, if any, needs to be backed out and reclassified as a current liability.

- “Notes payable” and “Bonds payable” are common examples of long-term liabilities.

Key Terms

- current

-

A length of time less than one year (12 months) into the future.

- Long-term

-

A length of time greater than one year (12 months) into the future.

- long-term liabilities

-

obligations of the business that are to be settled in over one year

- long-term investment

-

putting money into something with the expectation of gain, usually over multiple years

- liability

-

An obligation, debt, or responsibility owed to someone.

Long-term liabilities are debts that become due, or mature, at a date that is more than a year into the future. An example of this is a student loan. Let’s say John, a freshman in college, obtains a student loan for 25,000 and the bank does not require loan payments until 6 months after he graduates, i.e. 4.5 years after the loan was originated. This is an example of a long-term liability.

“Notes Payable” and “Bonds Payable” are also examples of long-term liabilities, and they often introduce an interesting distinction between current liabilities and long-term liabilities presented on a classified balance sheet.

Let’s say Company X obtains a 100,000 Note Payable that requires 5 annual payments of 20,000 starting 1/1/14. On Company X’s 12/31/12 balance sheet, a long-term liability for 100,000 would be reported, but what about the balance sheet as of 12/31/13? Since Company X is required to make a 20,000 payment on 1/1/14, which is less than one year away, a current liability of 20,000 and a long-term liability of 80,000 would be reported on its balance sheet as of 12/31/13.

Continuing one year forward, Company X would report a current liability of 20,000 and a long-term liability of 60,000 on its balance sheet as of 12/31/2014.

Sallie Mae facilitates several long-term liabilities

Student Loans are a prime example.

What this example presents is the distinction between current liabilities and long-term liabilities. Despite a Note Payable, Bonds Payable, etc., starting out as a long-term liability, the portion of that debt that is due within a year has to be backed out of the long-term liability and reported as a current liability.

See below for the balance sheet reporting treatment of the current and long-term liability portions of the Note Payable from initiation to final payment.

12/31/12 ……Current Liability: 0 ……………Long-Term Liability: 100,000

12/31/13 ……Current Liability: 20,000 ……Long-Term Liability: 80,000

12/31/14 ……Current Liability: 20,000 ……Long-Term Liability: 60,000

12/31/15 ……Current Liability: 20,000 ……Long-Term Liability: 40,000

12/31/16 ……Current Liability: 20,000 ……Long-Term Liability: 20,000

12/31/17 ……Current Liability: 20,000 ……Long-Term Liability: 0

12/31/18 ……Current Liability: 0 ……………Long-Term Liability: 0

11.4.2: Analyzing Long-Term Liabilities

Analyzing long-term liabilities combines debt ratio analysis, credit analysis and market analysis to assess a company’s financial strength.

Learning Objective

Summarize how to analyze a company’s long-term debt

Key Points

- Financial data used to calculate debt-ratios can be found on a company’s balance sheet, income statement and statement of owner’s equity.

- Benchmarking a company’s credit rating and debt ratios will assist an analyst in determining a company’s financial strength relative to its peers.

- Reading the footnotes contained in a company’s financial statements can be crucial as the footnotes often contain valuable information regarding long-term liabilities and other factors that could immediately impact the company’s ability to pay it’s long-term debt.

Key Terms

- insolvent

-

1. Unable to pay one’s bills as they fall due.2. Owing more than one has in assets.

- Creditworthy

-

1. Deemed likely to repay debts.2. Having an acceptable credit rating.

Analyzing Long-Term Liabilities

Long-term liabilities are obligations that are due at least one year into the future, and include debt instruments such as bonds and mortgages. Analyzing long-term liabilities is done for assessing the likelihood the long-term liability’s terms will be met by the borrower. After analyzing long-term liabilities, an analyst should have a reasonable basis for a determining a company’s financial strength. Analyzing long-term liabilities is necessary to avoid buying the bonds of, or lending to, a company that may potentially become insolvent.

How is Long-Term Liability Analysis Performed?

Analyzing long-term liabilities often includes an assessment of how creditworthy a borrower is, i.e. their ability and willingness to pay their debt. Standard & Poor’s is a credit rating agency that issues credit ratings for the debt of public and private companies. As part of their analysis Standard & Poor’s will issue a credit rating that is designed to give lenders and investors an idea of the creditworthiness of the borrower. The best rating is AAA with the worst being D. Please consult the figure as an example of Standard & Poor’s credit ratings issued for debt issued by governments all over the world.

World countries Standard & Poor’s ratings

An example of the credit ratings prescribed by Standard & Poor’s as a result of their respective long-term liability analysis for debt issued at the national government level. Countries issue debt to build national infrastructure. Look how expensive it is to raise capital for such projects based on geographic region.

In addition to credit rating agencies such as Standard & Poor’s, analysts can use debt ratios to help benchmark a company to it’s industry peers. Comparing a company to its peers will give an analyst perspective about what is considered normal or abnormal for a respective industry. Popular debt ratios include: debt ratio, debt to equity, long-term debt to equity, times interest earned ratio (interest coverage ratio), and debt service coverage ratio. Data used to calculate these ratios are provided on a company’s balance sheet, income statement, and statement of changes in equity. Typically, company’s present liabilities with the earliest due dates first.

Debt Ratio:

Debt to Equity Ratio:

Long-Term Debt to Equity Ratio:

Times Interest Earned Ratio (aka Coverage Ratio):

Debt Service Coverage Ratio:

There is more to analyzing long-term liabilities than simply reading a company’s credit rating and performing independent debt ratio analysis. In addition, an analyst needs to consider the overall economy, industry trends and management’s experience when forming a conclusion about the strength or weakness of a company’s financial position. When gathering information, an analyst should always read the footnotes contained in financial statements to determine if there are any disclosures related to long-term liabilities or other factors that may impact the company’s ability to pay it’s long-term obligations.

11.4.3: Debt-to-Equity Ratio

The Debt-to-Equity Ratio is a financial ratio that compares the debt of a company to its equity and is closely related to leveraging.

Learning Objective

Summarize how to calculate a company’s debt to equity ratio

Key Points

- Debt and equity have very distinct pros and cons.

- The composition of debt and equity and its influence on the value of a firm is a much debated topic.

- Debt and equity book values can be found on a company’s balance sheet, and the debt portion of the ratio often excludes short-term liabilities.

Key Terms

- equity

-

Ownership interest in a company, as determined by subtracting liabilities from assets.

- debt

-

Money that one person or entity owes or is required to pay to another, generally as a result of a loan or other financial transaction.

Debt-to-Equity Ratio

The Debt-to-Equity Ratio is a financial ratio indicating the relative proportion of shareholder’s equity and debt used to finance a company’s assets, and is calculated as total debt / total equity.

In order to obtain assets used in operations, a company will raise capital through either issuing shareholder’s equity (e.g., publicly traded common stock) or debt (e.g., notes payable). Stakeholders, which include investors and lending institutions, provide companies with capital with an expectation that those companies generate net income through their respective operations.

Debt is typically a long-term liability that represents a company’s obligation to pay both principal and interest to purchasers of that debt.

Equity represents ownership of a company, and does not include any agreed upon repayment terms.

Each form of raising capital has its own set of pros and cons. Interest payments on debt are tax deductible, while dividends on equity are not. Returns to purchasers of debt are limited to agreed- upon terms (i.e., interest rates), however, they have greater legal protection in the event of a bankruptcy. The returns an equity holder can achieve have unlimited upside, however, they are typically the last to be paid in the event of a bankruptcy.

Calculating the Debt-to-Equity Ratio

Calculating a company’s debt to equity ratio is straight forward, and the debt and equity components can be found on a company’s respective balance sheet. For more advanced analysis, financial analysts can calculate a company’s debt to equity ratio using market values if both the debt and equity are publicly traded.

When used to calculate a company’s financial leverage , the debt-to-equity ratio includes only long-term liabilities in the numerator and can even go a step further to exclude the current portion of the long-term liabilities. This means that other short-term liabilities, such as accounts payable, are excluded when calculating the debt-to-equity ratio.

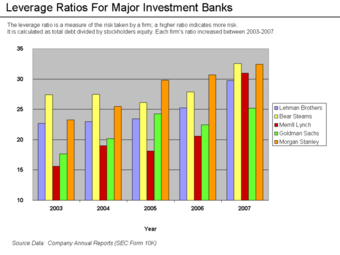

Leverage Ratios

Graph of how infamous investment banks were leveraged prior to the credit crisis of 2008.

11.4.4: Times Interest Earned Ratio

Times Interest Earned Ratio = (EBIT or EBITDA) / (Required Interest Payments), and is indicative of a company’s financial strength.

Learning Objective

Explain how a company uses the times interest earned ratio

Key Points

- Times Interest Earned Ratio is the same as the interest coverage ratio.

- The higher the Times Interest Earned Ratio, the better, and a ratio below 2.5 is considered a warning sign of financial distress.

- A company will eventually default on its required interest payments if it cannot generate enough income to cover its required interest payments.

Key Terms

- Interest

-

The price paid for obtaining, or price received for providing, money or goods in a credit transaction, calculated as a fraction of the amount of value of what was borrowed.

- times interest earned ratio

-

either EBIT or EBITDA divided by the total interest payable

- EBIT

-

Earnings before interest and taxes.

- EBITDA

-

Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

Times Interest Earned Ratio

The Times Interest Earned Ratio indicates the ability of a company to meet its required interest payments , and is calculated as:

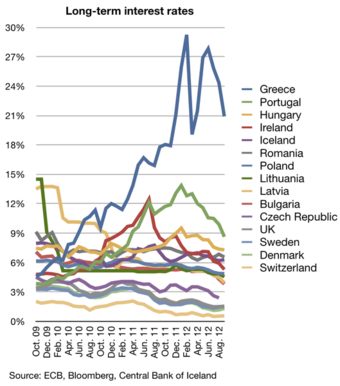

Long-Term Interest Rates

The Times Interest Earned Ratio is an indication of a company’s overall financial health.

Times Interest Earned Ratio =

Earnings

before Interest and Taxes (

EBIT

) / Interest

Expense

.

Earnings before Interest and Taxes (EBIT) can be calculated by taking net income, as reported on a company’s income statement, and adding back interest and taxes.

Analysts often use “Operating Income” as a proxy for EBIT when complex accounting situations, such as discontinued operations, changes in accounting principle, extraordinary items, etc., are reported in a company’s financial statements. Analysts will sometimes use EBITDA instead of EBIT when calculating the Times Interest Earned Ratio. EBITDA can be calculated by adding back Depreciation and Amortization expenses to EBIT.

The Times Interest Earned Ratio is used by financial analysts to assess a company’s ability to pay its required interest payments. The higher this ratio, or the more EBIT a company can produce relative to its required interest payments, the stronger the company’s creditworthiness and overall financial health are considered to be.

For example, if Company X’s EBIT is 500,000 and its required interest payments are 300,000, its Times Interest Earned Ratio would be 1.67. If Company A’s EBIT is 750,000 and its required interest payments are 150,000, itsTimes Interest Earned Ratio would be 5. Comparing the respective Times Interest Earned Ratios would lead an analyst to believe that Company A is in a much better financial position because its EBIT covers its required interest payments 5 times, relative to Company X, whose EBIT only covers its required interest payments 1.67 times.

If a company’s Times Interest Earned Ratio falls below 1, the company will have to fund its required interest payments with cash on hand or borrow more funds to cover the payments. Typically, a Times Interest Earned Ratio below 2.5 is considered a warning sign of financial distress.

11.4.5: Being Aware of Off-Balance-Sheet Financing

Off-Balance-Sheet-Financing represents rights to use assets or obligations that are not reported on balance sheets to pay liabilities.

Learning Objective

Explain what constitutes an off-balance-sheet financing item

Key Points

- Off-Balance-Sheet-Financing represents financial rights or obligations that a company is not required to report on their balance sheets.

- Off-Balance-Sheet-Financing can have a substantial effects on a company’s financial health: Enron is a great example of this.

- An analyst should always read the footnotes contained in the financial statements as they often either disclose off-balance-sheet-financing directly or provide enough information to determine if the company could potentially enter into off-balance-sheet-financing arrangements.

Key Terms

- off-balance-sheet financing

-

capital expenditures financed and classified it in such a way that it does not appear on the company’s balance sheet

- operating lease

-

A lease whose term is short compared to the useful life of the asset or piece of equipment being leased.

- subsidiary

-

A company that is completely or partly owned and partly or wholly controlled by another company that owns more than half of the subsidiary’s equity.

Off-Balance-Sheet-Financing is associated with debt that is not reported on a company’s balance sheet. For example, financial institutions offer asset management or brokerage services, and the assets managed through those services are typically owned by the individual clients directly or by trusts. While these financial institutions may benefit from servicing these assets, they do not have any direct claim on them.

The formal accounting distinctions between on and off-balance sheet items can be complicated and are subject to some level of management judgment. However, the primary distinction between on and off-balance sheet items is whether or not the company owns, or is legally responsible for the debt. Furthermore, uncertain assets or liabilities are subject to being classified as “probable”, “measurable” and “meaningful”.

An example of off-balance-sheet financing is an unconsolidated subsidiary. A parent company may not be required to consolidate a subsidiary into its financial statements for reporting purposes; however the parent company may be obligated to pay the unconsolidated subsidiaries liabilities.

Another example of off-balance-sheet financing is an operating lease, which are typically entered into in order to use equipment on a short-term basis relative to the overall useful life of the asset. An operating lease does not transfer any of the rewards or risks of ownership, and as a result are not reported on the balance sheet of the lessee. A liability is not recognized on the lessee’s balance sheet even though the lessee has the obligation to pay an agreed upon amount in the future.

It is important to consider these off-balance-sheet-financing arrangements because they have an immediate impact on a company’s overall financial health. For example, if a company defaults on the rental payments required by an operating lease, the lessor could repossess the assets or take legal action, either of which could be detrimental to the success of the company.

Jeffrey Skilling

Jeffrey Skilling is the former CEO of Enron, which was notorious for it’s use of off-balance-sheet-financing.